Receive free United Auto Workers updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest United Auto Workers news every morning.

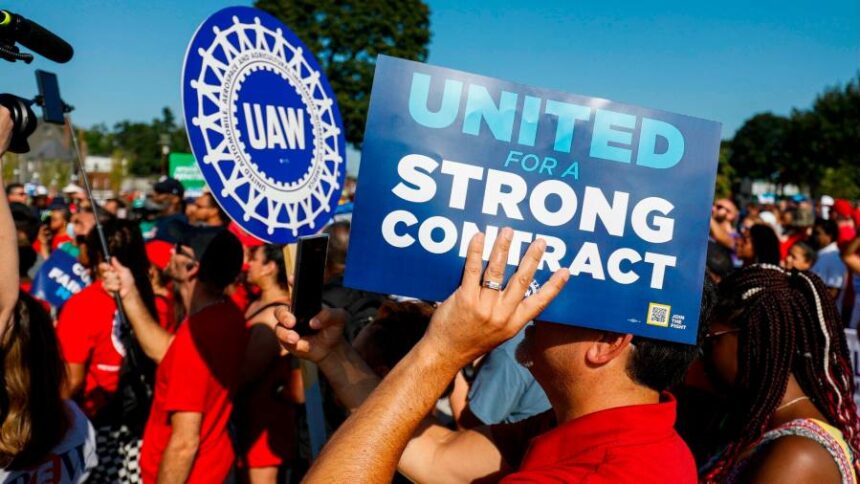

Auto workers and the top three Detroit carmakers are hurtling towards a strike that could deliver a multibillion-dollar blow to the US economy and complicate Joe Biden’s re-election campaign.

Two months into bargaining and the United Auto Workers and manufacturers remain far apart on how much the 150,000 autoworkers at Ford, General Motors and Stellantis should be paid.

The current contract expires at 11:59pm on Thursday, raising the possibility that the UAW could launch a strike against one, two or all three carmakers. It has never struck against all three in its 88-year history.

A 10-day strike against them all has the potential to cause a $5bn economic loss, costing both strikers and manufacturers hundreds of millions, according to Michigan consultancy Anderson Economic Group. It also could create problems for Biden, who has touted his pro-labour credentials, by forcing him to publicly pick a side in a dispute.

“This whole thing is going to be a mess,” said John Truscott, a Republican strategist in Michigan. “President Biden has to be very careful in how he approaches this. He has been very supportive of labour, but if this stretches out, he’s going to own it as far as the economic impact.”

Presidential politics, the auto industry’s shift towards electric vehicles and a new, outspoken leader at the UAW have made this year’s negotiation between the union and carmakers unusually tense. The UAW has proposed raising workers’ wages by 46 per cent over four years, reinstating cost of living adjustments and ending the two-tiered employment structure that privileges longtime employees with better pay and benefits than new hires.

Pay for UAW employees starts at $16.67 per hour for temporary workers and tops out at $32.32 per hour, according to Kristin Dziczek, a policy adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. (At 40 hours per week, that ranges from $35,000 to $67,000 a year.) Labour costs per employee, including all compensation, statutory costs and retiree benefits, are estimated at $66 per hour.

The Detroit Three’s share of the US auto market has fallen from 67 per cent in 1999 to 39 per cent today. Autoworkers made significant concessions during the Great Recession and the bankruptcies that followed at GM and Chrysler, now known as Stellantis. They went on strike in 2019 against GM for nearly six weeks, costing the company $3.6bn.

The three carmakers have proposed, over the life of the contract, pay increases for their workers ranging from 9 per cent to 14.5 per cent, with one-time payments that range from $10,500 to $12,000. Ford and GM also offered lump sum payments equal to 6 per cent of wages.

The UAW has pointed to carmakers’ profits to support their demands for higher pay. Ford, Stellantis and GM have booked a combined $161bn in net income in the past decade. UAW president Shawn Fain said on Friday in a video that “while the Big Three executives and shareholders got rich, UAW members got left behind”.

This negotiation, unlike in the past, has largely been conducted in public, which can lock both sides into their positions, said Marick Masters, a labour relations professor at Michigan’s Wayne State University. The union also has filed unfair labour practice charges against the companies with the National Labor Relations Board, signalling its aggressiveness.

“It will take an extraordinary turn of events to avoid a strike at this point,” he said.

Biden said last week he did not think a strike would happen, prompting Fain to reply: “He must know something we don’t know”.

White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said on Thursday that the president is “an optimist” who “believes in collective bargaining . . . In some of the most contentious situations, we’ve seen it work”.

Biden calls himself “the most pro-union president” Americans have seen, and his appointees to the National Labor Relations Board, a federal agency that protects workers’ right to join together to improve wages and working conditions, have resulted in a pro-labour majority. Still, he has spent his career as a centrist, and the typical presidential script for strikes is neutrality coupled with warnings about harm to consumers, said Jason Kosnoski, a professor who studies politics and labour at the University of Michigan-Flint.

Only 11 per cent of the US workforce is unionised, but inequality and stagnant wage growth has contributed to a surge of enthusiasm for unions, particularly among the young. This has made it “very difficult for the president to figure out how to go down the middle of the road”, Kosnoski said.

Fain said on Wednesday that Biden will need “to pick a side”. Michigan is a critical battleground state that voted for former President Donald Trump in 2016 and Biden four years later. It also has a seat in the finely balanced US Senate up for grabs in 2024. If Biden sides against the union it could discourage the state’s conservative-leaning Democrats from voting, Kosnoski said, as well as depress youth turnout nationwide.

Biden’s standing with labour is stronger than former Democratic presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. If the UAW secures a good deal for members and Biden supports it, he could benefit, said Susan Demas, a former Democratic strategist who is now editor of the non-profit news site Michigan Advance. So far the UAW has withheld its endorsement in the presidential race.

But Fain has shown he is unafraid of confrontation, she said.

“If he doesn’t feel the president is in their corner enough, that could create a pretty damaging rift in the Democratic party with one of its core constituencies, which is something that President Biden does not need going into 2024.”

Additional reporting by Lauren Fedor in Washington