The International Energy Agency last week said demand for all three major fossil fuels will peak this decade. Even beyond a crass “go woke, go broke,” many investors just don’t agree, and the replacement sources have their own issues. Surging costs have put key U.S. offshore wind projects in jeopardy, as a writedown from Ørsted brought into view, as nuclear projects globally also run into a myriad of cost and operational issues.

And even if you do agree that oil is near its peak, the ESG movement is limiting both the money and places that can be drilled, notes famed investment author John Mauldin. “Economics 101 says that if you reduce a supply of something that has an increasing demand the price is going to rise,” says Mauldin, who it should be noted is affiliated with an independent oil and gas operator.

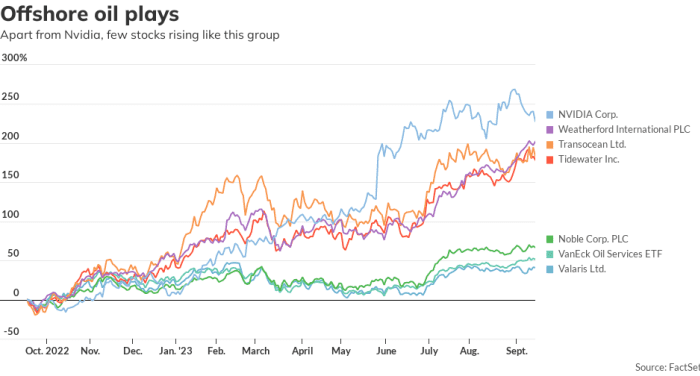

And that’s what has happened, particularly for offshore oil plays. The VanEck Oil Services ETF

OIH

has shot up 51% over the last 52 weeks, a period in which the S&P 500 has gained 15%. The stock of one oil services company, Weatherford International

WFRD,

has surged 202% over that time frame, a period in which Nvidia

NVDA,

shares have gained 228%. Transocean

RIG,

and Tidewater

TDW,

are pretty close to tripling their value over the last 52 weeks.

Not that anyone seems to care. Check out this photo from a Barclays offshore oil conference, which at least for one session was filled with empty chairs.

Rupert Mitchell, the author of the Blind Squirrel Macro blog, is focused on owners and operators of oil rigs or drill ships, their support vessels, and specialist service providers, with a combined market cap of $30 billion. Valaris

VAL,

Noble

NE,

and Weatherford each have emerged from bankruptcy with limited to no debt, while Transocean is debt-ridden but has the largest number of high-end assets, putting it in position to be a first mover of taking advantage of rising day rates. Tidewater is a leader in the platform supply vessel market.

His argument is simple — there’s high utilization rates, of more than 90%, and climbing day rates, which as it sounds is just the daily cost for drilling. At the same time, the offshore companies are trading at as much as an 80% discount to the value of their replacement cost, which prevents new equipment from being built. Shipyards, burned by the sector in the past, are focusing instead on hot sectors like liquified natural gas carriers.

“Bottom line – no new drill ships, floaters, jack-ups, PSVs etc. are going to get built until day rates have spent a reasonable amount of time way above current levels (to make newbuild economics begin to look sensible). We are a way off that point. Oilfield equipment and services players with low average age fleets are going to increasingly become price-makers,” he writes.

Best of the web

How to read the automakers’ offers.

Misreading Adam Smith spawned deaths of despair.

A real-life succession drama at LVMH

MC,

where 74-year-old Bernard Arnault has five children, all in the business.

The chart

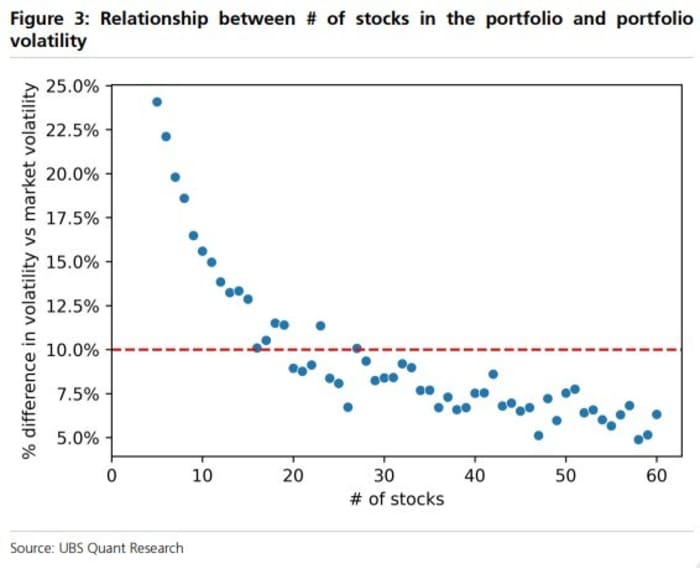

It takes 24 stocks to reduce portfolio volatility to within 10% of the market volatility over the last five years, according to calculations from quantitative strategists at UBS. They ran similar tests going back to 2009, and found 28 was the median number that brought portfolio volatility to within 10% of the market’s. Granted, UBS tested stocks were picked randomly and without regards to a diversification aim.

Random reads

People are watching pirated movies on TikTok — one 90-second clip at a time.

The host of a popular podcast on Rome is quizzed about the viral trend on why men are obsessed with the Roman Empire.

No Fun League was trending again after a New England Patriots lateral to an offensive lineman on a desperation fourth-down play was somehow ruled short of the sticks.

Need to Know starts early and is updated until the opening bell, but sign up here to get it delivered once to your email box. The emailed version will be sent out at about 7:30 a.m. Eastern.

Listen to the Best New Ideas in Money podcast with MarketWatch financial columnist James Rogers and economist Stephanie Kelton.