By the time Fumio Kishida hosted dinner on Thursday for BlackRock founder Larry Fink and sovereign wealth funds executives — according to one account, those in the room oversaw a combined $18tn of investments — Japan’s prime minister had a well-rehearsed pitch for his country.

Kishida has criss-crossed Tokyo during a “Japan Weeks” government campaign this week, popping up everywhere from a gathering of US and Japanese business leaders to a responsible investment conference and a trade union convention.

At every turn he delivered a core message: that global investors should finally turn bullish on Japan.

Kishida has pointed out that the economy and wages are stronger after decades of flirting with deflation and stagnant growth; that stock prices are near a 33-year high; and that Japan is poised to make good on a 20-year-old “from savings to investment” slogan, with a shake-up of its asset management industry and an expansion of tax-exempt investment vehicles to unlock $14tn of household savings.

Channelling such huge assets into investments “will contribute to sustainable growth not only in Japan, but also on a global scale”, Kishida said.

A decade after the “Abenomics” programme started by former premier Shinzo Abe, including massive asset purchases by the Bank of Japan and corporate governance reform, the Kishida administration is trying to put in place what officials say is “the final piece of the puzzle” by making foreign investment easier and bringing more flexibility and mobility to a rapidly shrinking workforce.

“As time goes on, we are going to continue to see these constructive policies play out,” said Drew Edwards, a veteran Japan portfolio manager who runs GMO’s Usonian equity funds, and who was visiting Tokyo this week. “I have been studying this market since the eighties and without question, really positive things are happening.”

With the top managers of BlackRock, KKR, Blackstone and sovereign wealth funds such as GIC, Temasek and Norges Bank gathered to hear the prime minister’s pitch, the sense of optimism is widespread.

But veteran Japan investors also warn that the window is limited for the Kishida team to sustain global interest in the country, which has benefited from external factors such as global inflation — which has finally helped to lift Japan out of deflation — as well as the big gap between interest rates in Japan and the US, and geopolitical uncertainty over China.

“Japan looks like an investment sweet spot right now, partly because of China and partly because of what is changing at many companies. But people need to be confident that this is long-term,” said the chief executive at one large Japanese company.

“The investors here this week are not here to trade Japan — they are looking for whether these positive things they see now are still going to be in place three, five even 10 years from now.”

In a sign of the underlying challenges for investors, the Japanese government had to intervene with messages and money to support its currency, stock and bond markets, even as Kishida carried out his promotional activities.

On Wednesday, the BoJ purchased nearly $13tn of government debt as yields on benchmark bonds hit their highest mark in a decade. On the same day, the central bank also bought ¥70.1bn ($472mn) of exchange traded funds, stepping into the market for the first time since March after the Topix index fell 2.5 per cent.

The yen, meanwhile, bounced higher after falling past the closely watched ¥150 to the dollar level, prompting brief speculation that Japanese authorities might have intervened after weeks of verbal warnings.

Privately, senior government officials admit that this may be Japan’s “final chance” to drive a meaningful reallocation of global money into the Japanese market.

Masatoshi Kikuchi, chief equity strategist at Mizuho Securities, said Japanese life insurers and pension funds actually planned to cut exposure to domestic equities. “As life insurers think their equity portfolios have big home country bias, they are increasing foreign equities,” he added.

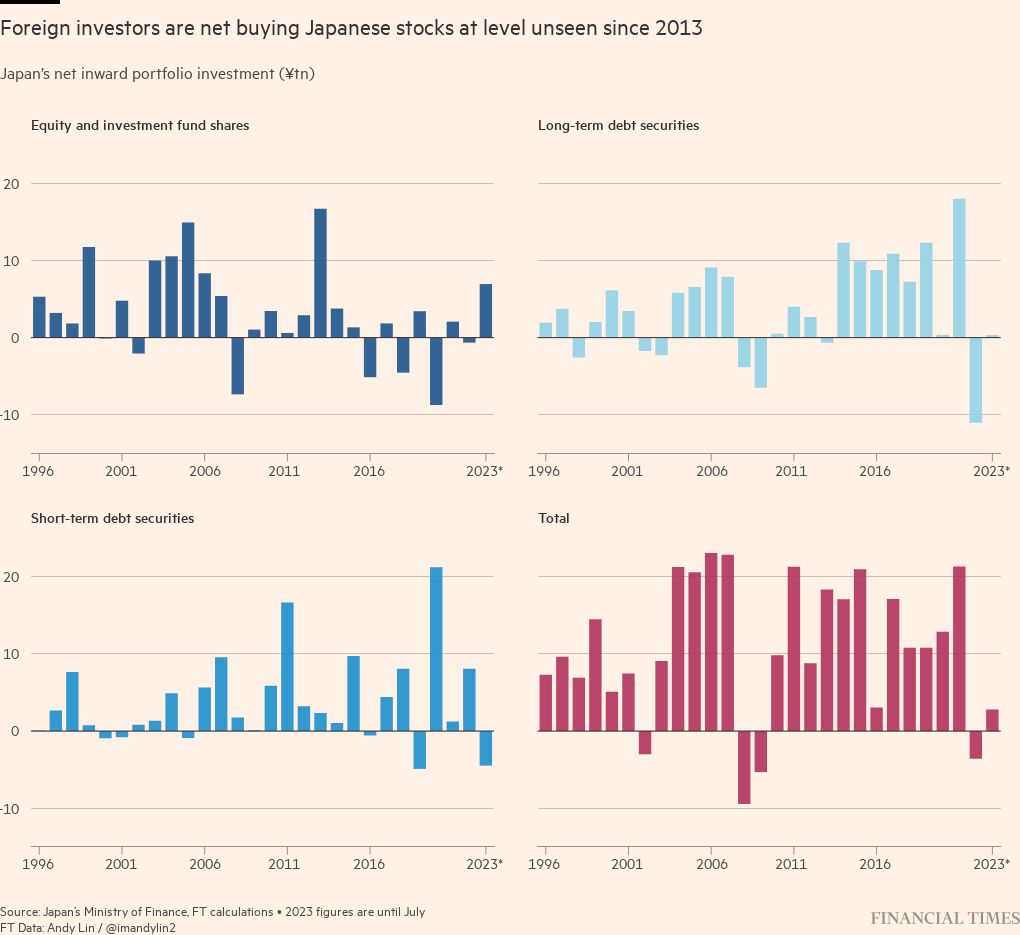

According to Edwards, most international managers of active funds are still “materially underweight” on Japanese equities after years of weak performance. “You have to experience [the change] yourself — especially those who had bad experiences 20 years ago — and that takes some time,” he said.

Nomura, the Japanese investment bank, estimates that if non-resident investors were to completely eliminate their underweight position it would push up the Nikkei 225 index — which today stands at around 31,000 points — by 4,900 points.

Even before investors turn fully bullish, several factors spurring global interest in Japanese equities are starting to weaken, said London-based Eddie Cheng, of US asset manager Allspring Global Investments.

Central banks in the US and Europe are nearing the end of their rate hike cycle, meaning the yen could start to strengthen from next year if the interest rate gap between Japan and the US narrows. That would make Japan seem less of a bargain for foreign investors.

“In the medium term, we are much more cautious,” said Cheng, who retains some overweight position on Japan.

“We will see how much those external factors will start to pare down and how much actual growth Japan can generate to support the equity market. If corporate Japan is not doing anything using this period of time . . . and solely rely on external factors, I think it will be very difficult” to sustain global interest, he added.

Even as he promoted Japan’s attractions to foreign investors, Kishida was also making the transition message to his country. Speaking to Japan’s largest labour organisation on Thursday, he stressed that the economy was on the cusp of shifting from decades of cost cutting to investment in human capital.

“We have a chance for the economy to move to a new phase for the first time in 30 years,” Kishida said. “We must not miss this opportunity.”