The U.S. is facing a housing deficit of about 3.2 million units, and the situation is especially dire in urban areas like New York. It’s one of the reasons prospective homebuyers are finding it increasingly difficult to find affordable homes.

That’s led many cities and communities to consider changes to strict single-family zoning restrictions, which are correlated with high home prices, surging rents, and fewer housing starts. Many see the reversal of pervasive restrictions on multifamily construction across cities as a solution to the affordable housing crisis.

Zoning changes often face pushback from existing homeowners, as many fear a sudden drop in home equity, the rise of new skyscraper apartment buildings, increased traffic congestion, and higher crime. But a shift to “light touch density,” which would allow fourplexes or smaller multifamily buildings and accessory dwelling units (ADUs) to be built on land currently zoned for single-family homes, has the potential to increase housing availability and affordability without a substantially negative impact on current homeowners.

Duplexes Make a Difference in Palisades Park

The town of Palisades Park, New Jersey, has been building duplexes to replace old single-family homes since the 1980s, when an influx of Korean immigrants increased demand for housing in the area. While the town’s zoning laws allowed for two-unit homes on each lot since 1939, developers only began implementing the strategy when demand for new construction made it a profitable move.

A benefit of this type of density change, when compared to constructing large apartment buildings, is that it doesn’t require local government subsidies or complex planning. Yet, over time, it makes sense that replacing single-family homes with duplexes doubles the supply of housing. The population in Palisades Park has grown 40% since 1990, vastly outpacing population growth across the New York metropolitan area, and the resulting economic activity has revitalized the town’s Main Street.

As the duplexes typically replace deteriorating homes, their construction more than doubles the value of each lot. That has allowed Palisades Park to reduce its property tax rate over the decades—neighboring Leonia’s residents (where duplexes are illegal) paid taxes at double the rate of Palisades Park residents last year.

The town’s vibrant culture has also made it a desirable place to live, which may be why homes in the community sold for a median of $950,000 in March, according to Redfin.

A meaningful change in the supply of housing takes time, however, and with an annual redevelopment rate of about 2% of available and desirable plots of land, it could take many years for Palisades Park to become a town consisting entirely of duplexes. And despite the gradual and minimal change in density, some longtime residents expressed discontent that the area became less green and more crowded over the years, according to a local sociology professor.

Still, the sentiment of current residents of Palisades Park is generally positive, and the community is a far cry from the hustle and bustle of New York City. And while some suburban politicians claimed looser zoning restrictions would result in overcrowding akin to the Big Apple, it’s clear the changes in Palisades Park weren’t that drastic, and the flexibility of zoning laws still proved beneficial for the community.

A Wave of Zoning Changes in Cities and States

At least three-quarters of residential land in most cities is zoned only for single-family homes, rendering developers incapable of building sufficient multifamily housing to meet demand across the country. Many municipalities are therefore reconsidering whether strict zoning laws, which were initially intended to perpetuate racial segregation, may be an unnecessary obstacle.

For example, California passed several new policies requiring localities to allow ADUs and reducing obstacles to development. Colorado is also considering legislation that would allow the construction of ADUs in many areas. Advocates recognize ADUs as a means to provide more affordable housing to more people while also allowing homeowners the opportunity to collect rental income and offset rising housing costs.

Since 2017, the city of Minneapolis has been reforming its zoning rules, making it possible (and more affordable) to build apartment buildings. These changes have resulted in a 12% increase in the housing supply over a five-year period and stabilized rents relative to other parts of Minnesota.

The University of California, Berkeley’s zoning reform tracker shows the status of zoning reform initiatives across the country, from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Washington, D.C. More than 45 municipalities have approved ordinances allowing for ADU reform, according to the tracker. The interactive map makes it clear these efforts are popping up everywhere, in both red and blue states.

Cities have taken varying approaches, but most reforms are focused on allowing light touch density. These policies, as evidenced by thriving Palisades Park, are more likely to provide a compromise between building new housing and protecting the character of local communities.

Still, some attempts at zoning reform have been met with harsh resistance from homeowners. A group of homeowners in Austin, Texas, filed suit against the city, leading a judge to block several efforts to allow for more dense housing that met affordability requirements.

Zoning Reform Is Worthwhile, but It’s a Challenging and Incomplete Solution

Alongside zoning ordinances, a slew of obstacles prevent residential development in cities. Authorities may delay zoning reforms to review the environmental impact of new construction, for example. It’s a common practice that began in 1970s suburbs in an effort to stall new development.

Some requirements, such as building and fire codes, have evolved to become more burdensome for developers. Approval processes are often lengthy and, when combined with permitting fees and high construction costs, can make many projects economically infeasible.

To encourage new construction, cities must streamline these processes. What’s more, reforming local zoning codes may not impact development if other restrictions are in place. A meaningful increase in housing supply requires a careful review of every restriction that could prevent progress, like minimum lot size and building size requirements. For example, Minneapolis had to throw away parking requirements for zoning reforms to be effective.

Even in Houston, a city that has yet to enact zoning laws, inflexible requirements and workarounds present significant hurdles. Homeowners who oppose more dense housing have found ways to prevent development in their communities even without a zoning code. Residents can vote to designate their neighborhood as a historic district and enforce building restrictions that way, and affluent communities often impose private deed restrictions. The Houston City Council uses “buffering” ordinances and other rules to control what type of development is permitted in certain areas, essentially creating land use zones.

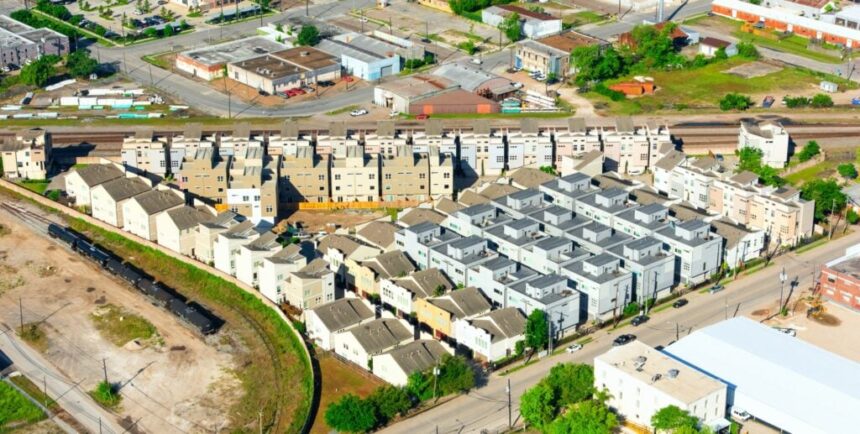

Houston has made changes that have ramped up new construction over the years, however. A policy that lessened the minimum lot size led to the construction of more than 34,000 townhomes in high-demand areas from 2007 to 2020, which expanded access to affordable housing for residents, according to Pew. The Houston Land Bank is converting tax-delinquent properties into affordable housing complexes.

The process of redeveloping a community, whether it’s zoned for single-family homes or burdened by other cumbersome restrictions, also takes time. It took years for the state of Oregon to pass legislation that would allow the construction of properties up to four units across the state and for cities to comply. Even with the new law in place, only a small share of parcels became ripe for redevelopment each year.

The city of Portland expects that the new zoning law will allow the construction of about 5,000 additional homes over 20 years in previously single-family neighborhoods. Governor Tina Kotek has always admitted that zoning reform would have a gradual impact on housing affordability.

But even if progress is slow, it’s worthwhile to reverse outdated zoning restrictions and related obstacles. Local governments have little control over high mortgage rates and rental inflation, but they can make it easier to build.

More than 83,000 ADUs have been permitted in California since reforms eased the costs and streamlined the process of ADU construction. That’s only a drop in the bucket compared to the 3.5 million new housing units the state expects to need by 2025, but it’s nevertheless an increase of more than 15,000% in permitted ADUs over a handful of years. Freddie Mac found the units cost less than one-third of the median home price in the area. In California, middle-income earners can afford most of the new units—a report notes that “ADU legalization triggered a boom in affordable housing at no cost to the taxpayer.”

The Bottom Line

Most cities host a community of homeowners who advocate maintaining strict zoning policies. They’re known as NIMBYs (which stands for Not in My Backyard). The impulse to preserve a neighborhood’s character is understandable, but the feared outcomes are often exaggerated, while the benefits are ignored.

Zoning reform doesn’t require the rapid bulldozing of parks and playgrounds. It merely gives developers more choices when redeveloping dilapidated houses, allowing them to fulfill the housing needs of other residents. Efforts at achieving light touch density, while slow-going and insufficient on their own, can nevertheless chip away at the unnecessary burdens developers face and promote an increase in housing supply over time.

Ready to succeed in real estate investing? Create a free BiggerPockets account to learn about investment strategies; ask questions and get answers from our community of +2 million members; connect with investor-friendly agents; and so much more.

Note By BiggerPockets: These are opinions written by the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of BiggerPockets.