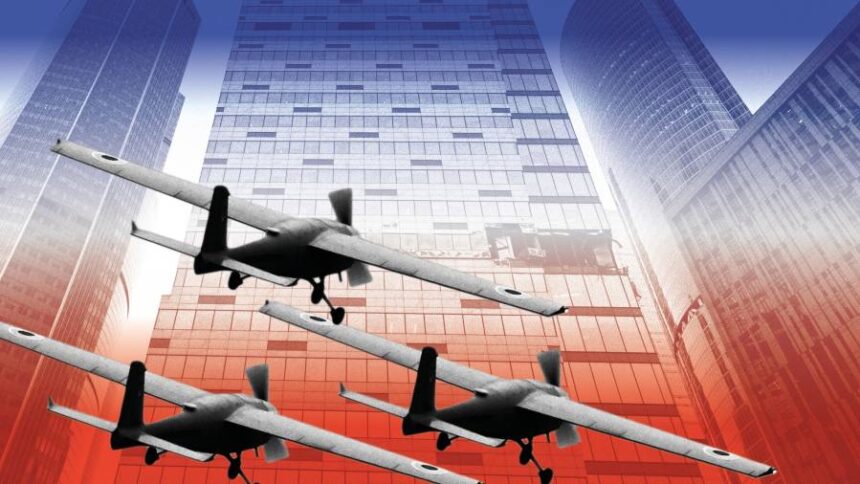

A shaky video posted online shows a drone swooping between the skyscrapers of the Moscow City business complex before exploding into the side of a glass tower. As a ball of fire erupts, a woman filming the scene screams: “We’re leaving tomorrow! We’re not staying here!”

The attack on Russia’s capital on July 30 was one of a series of drone strikes on the city that included another two days later and an assault on the Kremlin in May, as well as attacks on the country’s military infrastructure in the Black Sea and elsewhere.

Ukraine opened a new front on Friday, using a sea drone to hit a Russian naval vessel in the crude-exporting Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. That strike marked the first time Kyiv has targeted the oil infrastructure that funds Moscow’s invasion of its neighbour.

The drone attacks are part of efforts by Ukraine to wear Moscow down and bring its war close to home, analysts say.

“The main purpose of these attacks is to disprove [Russian president Vladimir] Putin’s narrative that this is just a ‘special military operation’ that’s about liberating Ukraine and has no impact on Russia,” said Kurt Volker, a former US ambassador to Nato. “They’re showing the Russian people that it’s a real war and Putin’s narrative is a lie.”

Andriy Zagorodnyuk, a former Ukrainian defence minister, said they sent a message to Russia that it was “not invincible”, and that even its capital and centres of powers were vulnerable. “This is very important, specifically for the Russian government,” he added. “In Moscow, they live their own life. Now they can be reached even [there].”

A video posted online shows the drone attack in the Moscow City business district © ViralBear/Reuters

A video posted online shows the drone attack in the Moscow City business district

There are signs that the strikes are having the desired effect. After Tuesday’s strike on Moscow City, Russian media reported some tenants were seeking office space elsewhere.

“The drones attacked the IQ tower and I work in the Eurasia tower right next to it,” said an IT company employee Ivan, referring to the hit on the building that houses the Russian trade, digital and economic development ministries. “I’m afraid of getting hurt just for coming to my office.”

“Everyone’s asking management what to do,” he added. “The only recommendation we received was not to stay in the office after 11pm.”

Russia’s Kommersant newspaper reported this week that Moscow City’s popularity would be affected and companies there, as well as the economic development ministry, had told staff to work remotely.

Some outside the business district were unconcerned. “These attacks don’t affect our lives at all, no one around me talks about them,” said Ksenia, a Moscow resident.

Military analysts say Kyiv is also using the attacks to distract Russia from its campaign inside Ukraine and frustrate its military, potentially forcing it to reallocate resources to Moscow.

There is no indication yet that the Kremlin has done any redeployment in response, although air defence systems were placed on the roofs of government and state security buildings in Moscow after the May attack.

While the latest strikes have not had a major strategic impact, they have sent a message about the Russian military’s inability to defend national airspace, a senior western military official said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

This could degrade Russian troop morale and help Ukraine’s counteroffensive, the official said: “[Morale] can be undermined directly, but also via soldiers’ families and the civilians that sustain the fight at home.”

But Kyiv, which has a policy of neither confirming nor denying the drone attacks, is also using the weapons mainly because it lacks other long-range options, analysts say.

“These attacks reveal Ukraine’s resilience in designing a . . . long-range strike deterrent to address a need not being met by [the west],” said Can Kasapoğlu, a non-resident senior fellow at Hudson Institute, a US-based think-tank.

Open-source intelligence suggested Ukraine had frequently used the UJ-22 drone made by Ukrainian unmanned aerial vehicle manufacturer Ukrjet to conduct such strikes, Kasapoğlu said. According to Ukrjet’s website, its UJ-22 UAV can fly for up to six hours and as far as 800km — enough to reach Moscow from the Ukrainian border.

Ukrainian blogger Ihor Lachenkov has recently raised $500,000 for the Beaver drone project, which Kasapoğlu said aimed to build “kamikaze” drones with a range of 1,000km.

Several analysts identified Beaver drones in videos published online during the Moscow strikes. Ukrainian actor Serhiy Prytula, whose eponymous foundation has raised some $120mn for military and humanitarian causes, recently published a video of himself on a runway beside several of the devices. “We have no idea what could fly to Moscow,” he said, grinning at the camera.

Zagorodnyuk said Ukraine’s long-range drone development was still in the early stages and that “at some point, the attacks will reach key [Russian military] facilities”.

Ukraine has been working on building a second-generation series of longer-range marine drones, known as Magura V5 with a range of 450 nautical miles. In May, one of them attacked the Russian spy ship Ivan Khurs in the Black Sea. Ukraine is also developing a drone torpedo, known as the Toloka.

“Ukraine has to fight its counteroffensive this way — slowly, attritting the Russians. It doesn’t have the mass to stick to a timetable following a tightly scheduled algorithm,” a western military official said.

Lieutenant General Ihor Romanenko, a former deputy head of Ukraine’s general staff, hinted there would be no respite for Russia. “Anyone who is questioning why Ukraine would conduct such strikes on Moscow should spend a few nights in Kyiv,” he said, referring to the Kremlin’s relentless bombardment of Ukraine’s capital.

“[Russia’s] population, which has supported Putin for more than 20 years, needs to start understanding that they are not protected by him and that something needs to be done with their leadership.”

Additional reporting by Polina Ivanova in Berlin