Liam Cotter’s childhood ambition was to be a millionaire. He dreamt of retiring before he turned 60, to pursue his passions for marathon running and music, and supporting himself with income generated by his lifetime savings.

But for years, his goal looked out of reach. The Irish accountant, who worked for more than a quarter-century at Kerry Group, one of the country’s biggest multinationals, had amassed a pension and some rental properties. But solo investments in gold and dotcom shares in the past had not worked out and he needed specialist investment help.

“I wanted a platform [to invest] — I want to reduce my worries, rather than increase them, especially when I retire,” says Cotter, 57, at his home in the southern city of Cork. He had long lived abroad but is now based in Ireland and was looking for advice on home soil.

The breakthrough was unexpected: as a sideline to his business career, Cotter had also worked as a fitness trainer. One of his clients, an investment adviser, helped him consolidate his assets — especially when he took redundancy in 2021. “He convinced me there was another way,” Cotter says. “Just hoping for the best with a pension fund your employer provided you” was never going to be enough.

Ireland’s newest wealth management company, Unio, which is backed by Canadian insurer Great-West Lifeco launched in April, responding to the demand for an industry to manage the burgeoning wealth in Ireland. Unio bought Cotter’s client’s business and two other wealth management groups and has €15bn in assets under management, of which two-thirds is pension business and the rest wealth.

Cotter, who now works at Brenntag, a German chemicals company, has his assets worth €2.5mn-€3mn invested with Unio.

When Ireland joined the EU in 1973, it was with the promise of a ticket to prosperity. But lacklustre economic performance in the 1980s led to nearly one in five people in the labour force being unemployed, driving a surge in emigration as workers — among them a newly graduated Cotter — looked for better prospects abroad.

Good times came in the mid-1990s, with a frenetic property boom. It ended with a banking industry crash that ushered in a recession and brutal austerity measures.

The country’s fortunes have now dramatically turned again, thanks to a corporate tax bonanza from a handful of multinational companies that has swollen state coffers, distorted EU growth data and prompted Dublin to prepare to establish a sovereign wealth fund to deal with budget surpluses expected to hit €65bn between now and 2025.

Unio strategic adviser Mike O’Sullivan, a former Credit Suisse executive and host of the Wealth Evolution podcast, says the ancient Celtic nation is an “old country with a new economy” based on growing prosperity.

Consultancy PwC predicts that assets under management in Ireland will grow from €3.66tn in 2022 to €6tn in 2027, equal to 10.3 per cent compound annual growth rate. This compares with 2.6 per cent and 2.2 per cent respectively for the UK and Channel Islands/Isle of Man over the same period, as predicted by Boston Consulting Group.

According to Credit Suisse, in 2021, Ireland had 176,000 people with wealth of more than $1mn (including property and financial assets) — a number that had increased more than 2.5 times in a decade. In addition, the country has nine billionaires with fortunes together totalling more than $37bn, according to Forbes’ list of the world’s richest people.

“Our business has grown exponentially over the past five or six years . . . There really wasn’t much wealth in Ireland 30 years ago and it’s changed dramatically over the past 10 or 15 years,” says Keith Ryan, head for Ireland at Julius Baer, Switzerland’s second-biggest bank, which manages the fortunes of individuals with millions of euros in assets. “If you look at the backdrop of our most recent history, it’s astonishing how Ireland looks and feels from a wealth point of view.”

He attributes the country’s changing fortunes not just to strong economic growth based on the international investment Ireland has attracted — particularly in the tech and pharma industries — “but also [to] a genuine spirit of entrepreneurship which has been hugely successful”.

The data from Credit Suisse shows overall wealth per adult in the country has doubled since 2000 to $251,337 per person on average — higher than Italy, Japan and South Korea and only fractionally behind Germany’s $256,985.

Ireland is a nation of avid savers. Although latest official figures show the rate of savings dropped in the first quarter to pre-pandemic levels, the ratio of saving to total domestic income was still 14 per cent, according to the Central Statistics Office (CSO).

Irish households still save more than they spend and “are still adding to their considerable deposits, they are just adding to wealth at a slower rate”, according to Peter Culhane, statistician in the National Accounts Analysis & Globalisation Division at the CSO.

Many of the increasingly affluent Irish plough their savings into bank deposits or buy and improve property, the CSO says. Financial investment only accounts for a small share of people’s wealth. “Our competitors are cash and the housing market,” says O’Sullivan.

In the past, those with $1mn and more in assets looked to larger financial centres such as London or Switzerland for wealth advice, but with rising numbers of Irish people with abundant income not tied up in property, there has been a growing opportunity for a domestic industry. Ireland’s biggest wealth management group is Davy, now owned by Bank of Ireland (BoI). Ireland’s largest bank by assets, bought the finance house in 2022 for €427mn.

BoI chief executive Myles O’Grady told the Financial Times the wealth business, including pensions, investment and insurance, was “an important part of our strategy, a source of growth for the business”. Strong net inflows had boosted assets under management by 7 per cent to €42bn in the first half of this year and O’Grady stressed “you don’t have to be rich to have a wealth product”.

Others also report growing appetite. “What we have seen over the past few years is an increased demand for those services. because of accumulated wealth in the country,” says Ian Quigley, head of investment strategy in Ireland at London-based RBC Brewin Dolphin, “whether that’s on the investment side or in the financial planning side.” RBC Brewin Dolphin, which was bought by the Royal Bank of Canada in an €1.8bn deal last year, has some €4bn assets under management in Ireland.

Quigley says that during the country’s Celtic Tiger boom of the 1990s, clients were more focused on property, adding that long-term financial planning and the construction of diversified portfolios has only really taken off since the financial crash.

In the three years after Ireland’s economic boom turned to bust in 2008, national income plunged 17 per cent. Cotter says the Celtic Tiger’s demise “left its wound in the Irish nation. Inevitably when people see things improving, there is a fear that it will all end in tears again”.

But it has also focused minds. Suzanne Cashin, financial planner at Brewin, says it “made people realise that property, like other assets, can go down, particularly if you’ve got a lot of leverage attached to it . . . That kind of reset people’s viewpoints on wealth management and what way they should invest their wealth to get the best returns”. As a result, “[having a trusted] counterparty became really important . . . people really liked that personalised approach,” she adds.

Cotter says: “There’s nothing special about me — maybe that’s all the more reason I need someone I can trust who are specialists at this kind of thing because I feel there are big risks to this.” He has 75 per cent of his portfolio invested in medium-risk assets, mainly stocks, bonds and some cash, and is not even remotely tempted by crypto.

In addition to aspiring Irish investors such as Cotter, continental clients and expatriate British investors based in the EU are also turning to Ireland because Brexit limits what UK-based wealth managers can do to seek business in the EU.

Wealth managers say London was for long the wealth management hub for the European timezone but Ireland — being English-speaking, part of the EU and having a common law legal system — is fast picking up business.

Quigley, at Brewin Dolphin, is also seeing a surge in the number of continental European clients. “That’s become a catalyst . . . in a year’s time, it could be quite material [to the business],” he says.

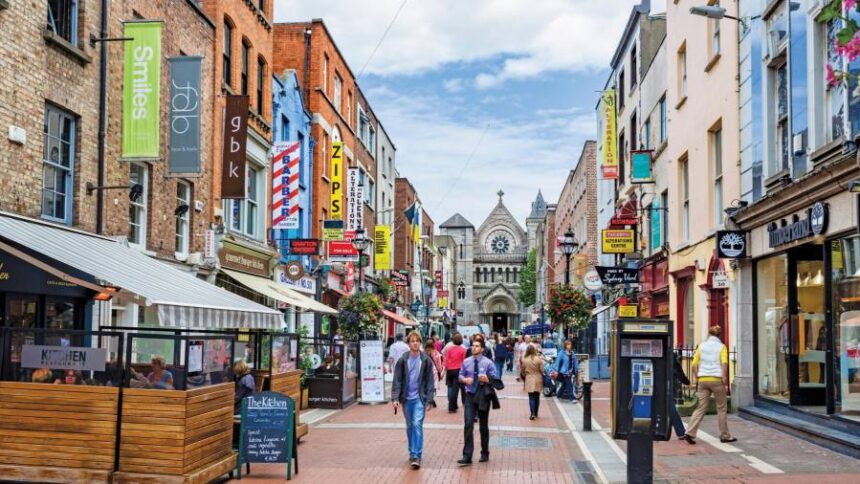

Overall, the industry is seeing rapid growth: Ryan said Julius Baer has notched up 30 per cent compound annual growth in assets under management in Ireland for the past five years and the trend is continuing this year. The expanding business has more than doubled its staff and the bank moved into a new office in central Dublin in July.

“There hasn’t been much intergenerational wealth in Ireland because there wasn’t much wealth to transfer,” Ryan adds. “The vast majority of our expansion relates to first generation younger entrepreneurs selling businesses . . . There is still some significant activity in M&A, particularly in tech engineering, healthcare, financial services. Notably the property sector has not been a big variable in that growth of wealth, which contrasts so dramatically with the Celtic Tiger era.”

The Irish have more income to invest, but the departure of some big-name companies such as buildings material group CRH from the Irish stock market has underscored the fact that domestic investment opportunities are limited. CRH is dropping its Dublin trading as part of the switch in its main listing from London to New York. As a result, wealth managers generally look to global investments.

But they hope growing personal fortunes in Ireland can be used to stimulate a domestic private equity and venture capital industry. For O’Sullivan, of Unio, “the challenge is educating people and getting them to think of wealth as a driver of the economy”.

Ryan says venture capital as a means to boost entrepreneurial success “is still undeveloped or under-developed. I think we need to look at regimes such as the US and the UK and see how we can encourage the wealth that has been created and to invest in the next wave of start-ups.”

Also, the new generation of Irish investors is seeking sustainable investments, O’Sullivan says. “The idea is that the client base will have modern, sophisticated portfolios of private assets that perhaps they wouldn’t normally get access to.” For Cotter, access to such investment platforms is crucial. Without that, he believes only a small percentage of those benefiting from Ireland’s booming economy will “be able to find the pot of gold in those opportunities”.

Ireland’s fast growing population, robust corporate tax receipts and its ability to attract investment bodes well for the industry. “I’m optimistic that what we’ve experienced in the last number of years is not the top,” says Ryan. “This has proper longevity.”

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment