When Alexandra Rodriguez asked her landlord to repair the fire alarm in her rented flat in south London, she did not expect his response to be an eviction notice. Yet he sent her a formal request to vacate the flat within two months — then re-advertised it at a rent nearly 40 per cent higher.

“They advertised the property on Rightmove at £1,800 per month . . . that’s why they got rid of us,” said the 37-year-old science technician, adding that she was still “emotionally and financially” recovering from being pushed out of her home.

Her experience echoes that of many Londoners who are being hit with surging rents or even evicted as landlords pass on pressure from higher interest rates. The private rented sector — on which the UK capital has become increasingly reliant over the past two decades — is particularly vulnerable to higher rates because of the prevalence of interest-only buy-to-let mortgages, which helped create legions of middle-class landlords.

Rents in London are at their highest level on record, far above those in the rest of the UK and higher than in many European capitals. London rents rose by a fifth between March 2020 and May 2023, with the median cost of a studio in Greater London reaching £1,275 per month, according to property agents Savills.

A boom in demand for tenancies is being fuelled by record immigration to the UK and a wave of students pushed into private rentals by a shortage of student accommodation, say experts.

Higher mortgage rates and the end of a government scheme supporting first-time buyers have meanwhile forced more would-be homebuyers into lettings, said Richard Donnell, head of research at Zoopla.

“The affordability of home ownership in London, where you need to be on a £100,000 income and [have] a £140,000 deposit to buy, means a lot of people are having to rent,” said Donnell. UK house sales are on track for their slowest year in more than a decade, according to Zoopla.

Soaring demand means tenants are competing fiercely for homes. Neil Short, head of London lettings at estate agent JLL, said they were entering bidding wars and offering to pay multiple months’ worth of rent upfront.

“I’ve been doing lettings for the best part of 20 years and only recently have I seen an instance where we’ve had to take a property off the market because within half an hour we generated viewings of 20 people,” said Short. “We were inundated with inquiries. We had to physically stop [them].”

Adding to the pressure, the stock of available homes to rent in London — already insufficient to meet demand — is at risk of shrinking after just starting to recover from a five-year low in 2022. About 4.8mn private landlords provide accommodation for a fifth of UK households, said Savills. Of those, more than 1mn are in Greater London, where they accommodate about 30 per cent of households.

Britain’s private rented sector boomed in the 2000s after the rollout of buy-to-let mortgages. London’s high reliance on interest-only loans has made it vulnerable to rising borrowing costs, which are putting landlords’ business models under strain.

The average two-year buy-to-let residential mortgage rate in the UK rose from 4.5 per cent in August 2022 to 6.6 per cent at the end of August 2023, according to Moneyfacts. That has hurt landlords within and outside London. Neil France, an Essex-based landlord with four buy-to-let properties, said the rises in monthly payments had been “horrific” and forced him to increase rents to avoid making a loss. “We have had to go out to all the families, sit down with all the tenants [and] explain to them the situation,” he said.

The hit to borrowers follows regulatory changes that had already dimmed the appeal of private rental investments. The UK government scrapped tax relief on buy-to-let mortgage interest in 2016, while landlords face the possibility of new energy efficiency requirements in the coming years, along with tougher regulation of the rental market.

“The impact of [the 2016 tax change] is really starting to be felt today, when you’ve got rates of 6 to 7 per cent that can’t be offset as an expense,” said David Fell, analyst at estate agent Hamptons.

Lenders repossessed 440 buy-to-let properties in the UK in the second quarter of 2023, up 7 per cent from the previous quarter, while a further 1,870 landlords were behind on repayments by a sum totalling more than 10 per cent of their outstanding loan, according to UK Finance.

“I cannot believe anybody would go into buy-to-let now,” said France. “I would question their sanity.”

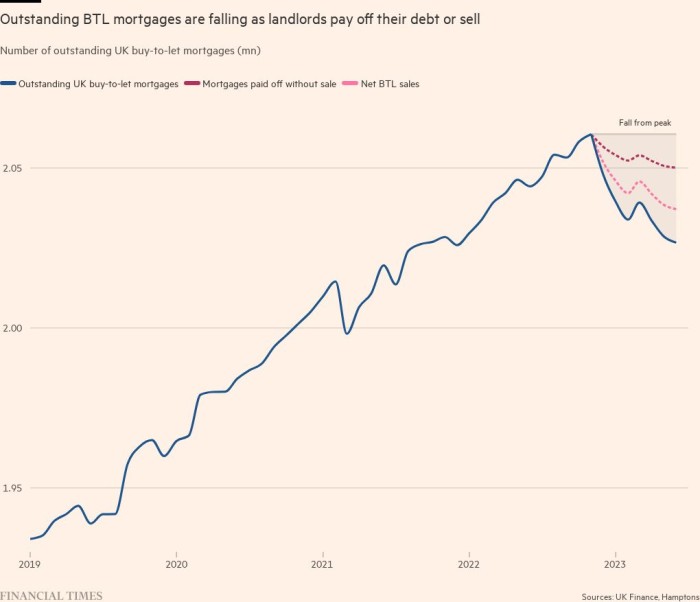

Outstanding buy-to-let mortgages have fallen this year as landlords pay off their debt or sell properties to avoid the blow from higher rates. In London, high mortgage costs make the returns on such properties lower than elsewhere. “Unfortunately, we are going to see a lot of old landlords selling up,” said Donnell.

Hamptons estimates that between one-third and half of homes sold by landlords remain in the private rented market. A sell-off therefore risks further squeezing supply, experts warn. That would pile pressure on to London’s most vulnerable tenants, many of whom rely on private rentals because they cannot access social housing.

About a quarter of UK tenants in the private rental sector receive government housing benefit, according to analysis of government data by Zoopla and the homelessness charity Crisis — the figure in London is 29 per cent.

“We haven’t built enough social housing over the last 20 years, so the private sector growth has absorbed unmet demand,” said Zoopla’s Donnell. “As soon as the rental market stops growing, it highlights a whole lot of problems.”

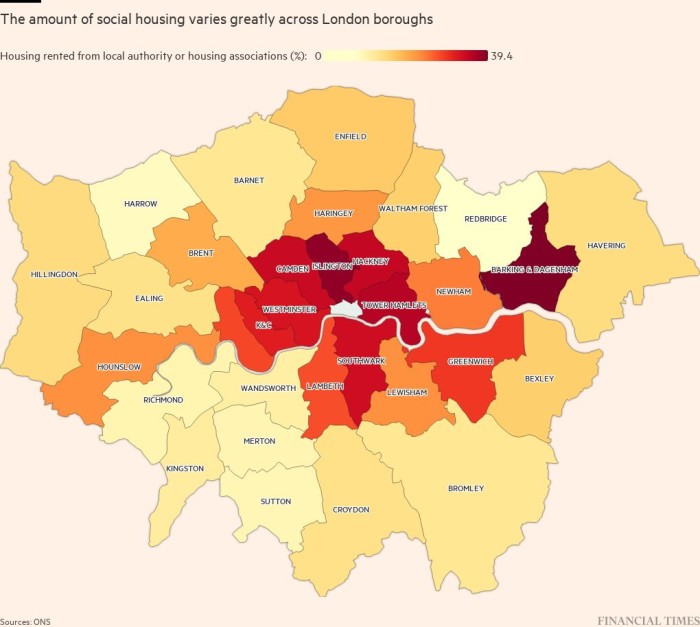

Within London, the proportion of households in social housing — homes provided by councils and not-for-profit housing associations at rents linked to incomes — varies widely by borough, from less than 10 per cent in Redbridge to almost 40 per cent in Barking and Dagenham.

Local housing allowances have not kept up with rising rents, so people on benefits cannot compete in the private rental market, said campaign group Generation Rent.

They also risk having to find new homes because landlords in England can evict tenants with two months’ warning without explanation from as little as six months into their tenancy.

Such evictions will be restricted under a renter’s reform bill that is going through parliament but the tougher rules have made slow progress since they were pledged in 2019. Generation Rent said loose regulation made low-income families especially vulnerable.

Rents are rising throughout London but are growing fastest on the city’s outskirts in boroughs such as Harrow, Sutton and Havering. “The big story in London is renters being pushed into outer London in search of affordability,” said Donnell.

Hair stylist Solomon, 29, spent weeks frantically looking for a room after his landlord gave him notice to leave his Camberwell flat. After repeatedly being outbid, he decided to cut his losses and move to Basingstoke in Hampshire.

“I can either spend lots of money to be in London — in a place I won’t be comfortable in with damp and mould that affects my mental health — or I take the plunge and move out of London and deal with commuting,” he said.

Solomon, whose commute to Peckham in south London now takes more than an hour, said leaving the capital was the only way he could live alone in a well-kept, functioning flat.

“My work and career is in London, all my friends are there, but the things I need at my stage in life are home and security,” he said. “London wasn’t able to provide that for me any more.”

Data visualisation by Chris Campbell and Martin Stabe

Extreme renting

This is the latest part of a series on Europe’s rental crisis: