Receive free German economy updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest German economy news every morning.

A sharp decline in carmaking fuelled a deepening downturn in German industry as production fell for the third consecutive month in July, intensifying pressure on the government to do more to lift the economy out of the doldrums.

The 0.8 per cent month-on-month decline reported by Germany’s statistical office exceeded the 0.5 per cent fall forecast by economists in a Reuters poll. It would have been even bigger without a rebound in energy and construction output in July. Production in Germany’s car-making sector fell 9 per cent.

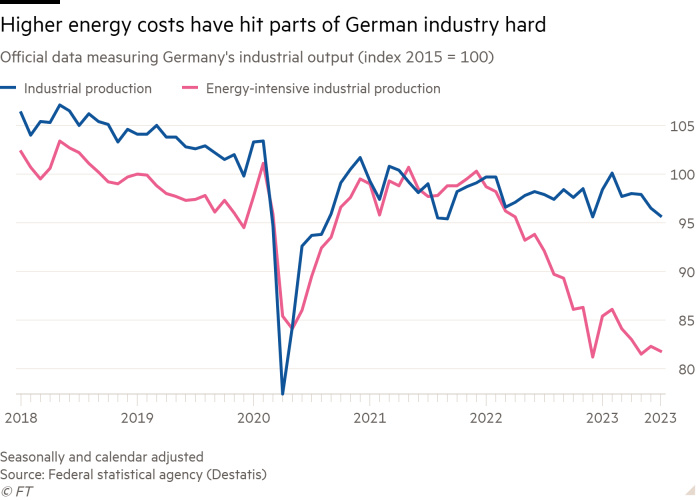

Europe’s largest economy has shrunk or stagnated for the past three quarters and its recovery from the coronavirus pandemic has been slower than the US or the overall eurozone, with higher energy prices, rising interest rates and a slowdown in trade with China — its second-biggest export market — hitting Europe’s industrial heartland particularly hard.

Ralph Solveen, an economist at German lender Commerzbank, said the continued decline in industrial production had affected “all manufacturing groups”, indicating it was likely to continue “contributing to a contraction of the German economy in the second half of the year”.

There are rising fears about German industrial groups shifting production abroad. BASF, the country’s leading chemicals company, chose to build a new €10bn petrochemicals plant in China and it is downsizing its sprawling headquarters on the banks of the Rhine in Ludwigshafen.

The German Chamber of Commerce and Industry recently found that 32 per cent of companies surveyed favoured investment abroad over domestic expansion.

“Germany’s industrial production continues its nosedive and even diehard pessimists are getting frightened,” said Carsten Brzeski, an economist at Dutch bank ING, who calculated German industrial production was still 7 per cent below its pre-pandemic levels.

The government has come under intense pressure to tackle the country’s economic woes. This week chancellor Olaf Scholz vowed to boost growth and banish the “mildew of bureaucracy” by speeding up digitalisation for online government services and e-invoices — areas in which Germany lags behind — and making it easier to found and grow start-ups.

Scholz has rejected the idea of a subsidised electricity price for energy-intensive companies or a large stimulus package to boost growth. Last week he unveiled plans for a €7bn package of corporate tax relief, which includes new rules on the depreciation of investment costs for construction, digitisation and green energy.

“The positive news is that the sense of urgency has finally increased,” said Brzeski. “Let’s now wait for more concrete policy action. Until then, stagnation in industry and the broader economy looks like the new normal.”

Destatis, the federal statistical agency, said the year-on-year decline in industrial production in July was 2.1 per cent. The most energy-intensive industries, such as chemicals, metals and glass, have suffered a bigger year-on-year fall of 11.4 per cent.

German manufacturers are working through their backlogs of orders but these are shrinking. New orders for German industry fell 10.7 per cent in July from the previous month, the biggest decline since the first pandemic lockdown shut many factories in April 2020.

“Though the backlog of unfilled orders is still high, it has been declining steadily so is unlikely to support production much longer,” said Franziska Palmas, an economist at consultants Capital Economics. “We expect production to drop further in the rest of the year and contribute to Germany falling back into recession.”

Another factor holding back many German companies is the shortage of labour. A survey of 9,000 companies in the country by the Ifo Institute last month found 43.1 per cent reported a shortage of qualified workers, an increase from the previous month but down from an all-time high of almost half of all companies last year.