Receive free Italian banks updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Italian banks news every morning.

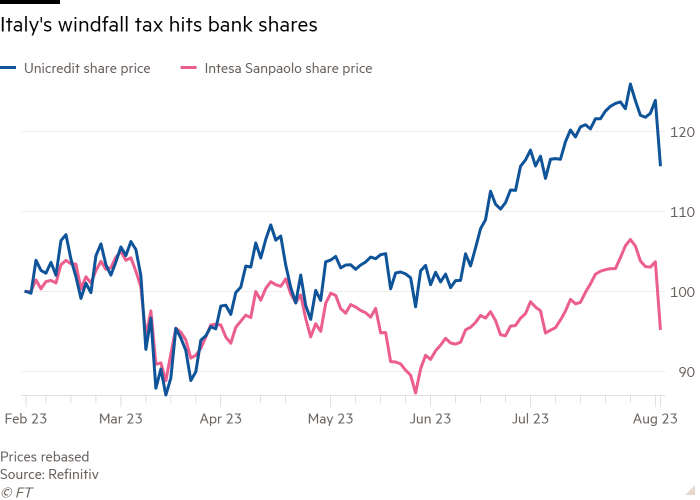

Italy’s rightwing coalition has sent bank shares tumbling with a surprise 40 per cent “windfall” tax on lenders’ profits resulting from higher interest rates.

The hasty measure unveiled late on Monday night came after bumper profits for lenders following rate rises, combined with political pressure on Giorgia Meloni’s government over the impact of inflation and higher rates on households.

One senior banking executive called the tax, which the finance minister had previously ruled out, a “cold shower”.

Shares in Intesa Sanpaolo and UniCredit, the country’s two largest banks, dropped 8.6 per cent and 5.9 per cent respectively by the close on Tuesday. Shares in state-owned Monte dei Paschi di Siena fell 10.8 per cent, while Banco BPM, the country’s third-largest bank, shed 9.1 per cent. BPER Banca, Mediobanca and Banca Generali were also down.

Analysts at Jefferies and Equita estimated the government could raise more than €4.5bn from the tax, higher than the €2bn to €3bn suggested by Italian officials. Intesa and UniCredit would be the largest contributors, analysts said, but the capital impact would be larger on smaller banks.

Analysts at Jefferies said, on average, the capital impact would be “sizeable but manageable”. The investment bank said the cost would amount to an average of 60 basis points on core tier one capital, a ratio used as a measure of banks’ financial health.

In a statement more than 24 hours after the measure was approved, the finance ministry said the levy could not exceed 0.1 per cent of each bank’s total assets “in order to safeguard lenders’ financial stability”.

Meloni’s government said it would use the sums raised by the levy, which still needs parliamentary approval, to fund measures to help families and small businesses.

Her administration, which took power last October, has criticised banks for failing to pass on interest rate rises to small savers. The levy follows moves by other European countries, such as Spain and Hungary, to impose windfall taxes on lenders.

Analysts expect the ill-received draft measure to be tweaked before parliamentary approval.

“The government was hoping to obtain €2bn-€3bn, and the Milan bourse just lost over €10bn on the news . . . not the smartest move,” said one senior banking executive, speaking on condition of anonymity.

The tax, approved in a cabinet meeting late on Monday night, will be applied to the net interest income generated from the gap between banks’ lending and deposit rates.

The European Central Bank has raised rates by 4.25 percentage points since last summer, increasing the benchmark deposit rate from minus 0.5 per cent to 3.75 per cent. But much of that increase has not been passed on by banks across the euro area to savers.

A draft text released by the government on Tuesday afternoon suggested the threshold for imposing the 40 per cent levy would be based on the difference between net interest income in 2021 and the figure for 2022 or 2023, whichever is larger.

Banks would pay the tax once their net interest income for the selected year exceeded 2021 by either 5 or 10 per cent. The one-off levy, due for payment by the end of June 2024, must secure parliamentary approval within 60 days.

Italian banks are expected to make 50 to 80 per cent more net interest income this year than in 2021, said a Milan analyst, speaking on condition of anonymity. Taking this into account, the 40 per cent levy would have a “devastating impact [on capital] for smaller banks”, they said.

Political analysts expressed dismay at the government’s clumsy handling of the announcement, which was delegated to Matteo Salvini, the deputy prime minister. Finance minister Giancarlo Giorgetti, a senior member of Salvini’s League party, did not attend Monday night’s news conference.

Italian officials and senior bankers in Milan said there were fractures within the government coalition over the levy, though the minister’s entourage denied that there had been internal disagreements.

“You don’t do these things — you don’t put a tax on the banks without telling them and without having the finance minister go on TV to explain it,” said Francesco Giavazzi, a Bocconi University economics professor who served as economic adviser to former prime minister Mario Draghi.

Italy’s five largest banks have reported aggregate profits of €10.5bn in the first half of 2023, up 64 per cent from a year earlier, according to rating agency DBRS Morningstar.

Salvini said in a press conference late on Monday that the tax was “common sense”.

Italy’s foreign minister Antonio Tajani appealed to the ECB last month to stop raising interest rates, saying higher rates were putting a strain on borrowers while failing to curb inflation.

Gross domestic product figures last week showed that Italy’s economic recovery had faltered during the second quarter.

Almost 1mn Italian families missed payments on loans and mortgages in March, totalling €14.9bn as soaring interest rates strained household finances, according to the national bankers’ association Fabi.

Additional reporting by George Steer