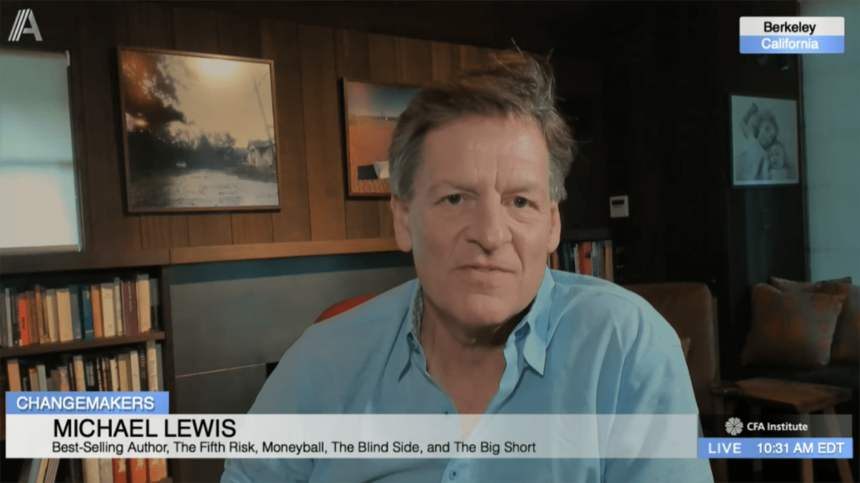

Michael Lewis can “untangle complex subjects like few others.” And few topics qualify as more complex — or more tragic — than the US response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the subject of his latest book, The Premonition: A Pandemic Story.

At the heart of Lewis’s narrative is a central question: Why did the United States fail in its response?

Lewis’s answer, which he detailed in a wide-ranging conversation with Planet Money‘s Mary Childs at the recent Alpha Summit by CFA Institute, is startling and provocative: “People were actually incentivized to create a bad pandemic response.”

To demonstrate what he means and to cull lessons for the world of finance, Lewis focused in on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US national public health agency, and the experience of the central character in his book: Charity Dean, MD, an expert in communicable disease outbreaks and the former assistant director for the California Department of Public Health. Dean was a key member of the executive team directing the COVID-19 outbreak response.

“Gut Check” for the United States

The United States has fared poorly in terms of COVID-19 cases and deaths. At the time of this writing, the country has recorded more than 33 million cases and about 600,000 Americans have lost their lives, according to data compiled by the New York Times. (A new study estimates the country’s COVID-19-related death toll to be much higher, at more than 900,000.)

“We have 4% of the world’s population and we have 20% of the deaths,” Lewis said. “No matter how you cut it, no matter how you dress it up, it is not a good response, it is not a good outcome.”

The US pandemic response is “a really serious gut check” for the nation, he said, especially since the country ranked first among 195 nations on the 2019 Global Health Security Index‘s survey of pandemic preparedness.

Was the US pandemic response doomed from the start? It certainly looks that way, according to Lewis.

Part of the problem was a decentralized approach to fighting the pandemic. As Tanya Lewis points out for Scientific American, “the U.S. government’s structure meant that much of the pandemic response was left up to state and local leaders. In the absence of a strong national strategy, states implemented a patchwork of largely uncoordinated policies that did not effectively suppress the spread of the virus.”

For a response to be effective, it must be unified, Michael Lewis said.

“You can’t have one state doing one thing, and another state doing another thing,” he said. “The lack of unification at the top probably doomed it from the start.”

And Lewis points the finger directly at the CDC.

“We have an enterprise called the Centers for Disease Control that actually isn’t set up to control disease,” he said. “This is putting it a little harshly, but if you had asked the Centers for Disease Control to maximize illness in America because of COVID-19, they might not have behaved all that differently from what they did.”

The CDC and Incentives

The problems at the CDC stem from misaligned incentives, according to Lewis, because institutions like the CDC have become politicized.

To understand what he means, we have to dial the clock back to around 1984.

At that time, Lewis explained, the CDC “was the gold standard for public health in the world,” run by career civil servants who were kept at arm’s length from the political process.

This meant the person at the helm could not be fired on a whim by the president and could focus on guarding public health.

But then something changed: In the mid-1980s, many federal government jobs transitioned from permanent career positions to presidentially appointed ones. This altered the incentive structure. Now, instead of being hired from a general pool of qualified candidates without regard to politics, staff are selected from a smaller, politically motivated pool.

Perhaps the worst issue of all with politically appointed jobs, Lewis said, is the short time horizon:

“You signal to the organization and person who is taking the job that this leader is not there very long, they’re going to be there at best as long as the person in the White House is there, and in fact the average tenure of these political appointees is 18 months to two years.”

Short-term appointees equal short-term incentives.

“Who on the planet would say it’s a good idea to make the CEO someone who everyone knows is going to be gone in 18 months to two years?” Lewis asked. “You’re not going to address long-term problems.”

Key Takeaway: Avoid short-term incentive structures.

How to Be a Charity Dean

While Lewis has only barbed words for the CDC, he finds a glimmer of hope in the form of Dean and a group of doctors called the Wolverines who had all worked in the White House at various times and had stayed in contact because of their efforts fighting disease outbreaks.

Dean was among a cohort of scientists and physicians who very early on sounded the alarm about the COVID-19 pandemic but were largely ignored.

As Lewis tells it, Dean emerged from a bumpy period in her life around the time she became a local public health officer in California. The story Dean insists on telling herself is a critical one and it can be summed up in one word: bravery.

“The story is she is responsible, even if she isn’t, for everything that has happened to her,” Lewis said. “She is going to embrace that responsibility and she’s going to insist on being brave even if it’s painful.”

Dean pens inspirational messages on post-it notes and plasters them throughout her home to remind herself of the importance of being brave. One of her favorite lines is “Courage is a muscle memory.”

Why is this important? What can others learn from her example?

What this allows her to do is recognize that sometimes what is holding her back is cowardice.

“Being aware when you are caving in to a kind of weakness becomes an art form,” Lewis said. “It becomes something that you develop a muscle memory for and if I’m teaching someone how to be her, I’d say develop that muscle memory.”

Key Takeaway: “Courage is a muscle memory.”

Probabilities vs. Narratives

Risk is a topic that Lewis often explores in his books. Regardless of the character or story, one element always strikes him: the disconnect between the people who manage risk well and the rest of the society.

“You would think markets would be more efficient,” Lewis said.

To illustrate his point, Lewis pointed to baseball, a game he covered in his classic Moneyball. Baseball has been pretty much played the same way for about 100 years and the players are doing their jobs in front of millions of people and have stats attached to their every move.

“You can price the risk of baseball players, and you could have done it a long time ago,” he said. “The fact that no one did it until the Oakland As come along and see stuff off-the-shelf that’s been written by Bill James and start thinking about it, it tells you there is something in the human brain that is very slow to think in the terms it needs to think about risks smartly.”

The main insight that Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky had about risk, which Lewis examines in The Undoing Project, is that people are “not probabilistic machines.” So what happens most of the time is that instead of calculating probabilities, people make decisions based on narratives.

And that observation can be applied to the COVID-19 calamity in the United States, Lewis said.

The narrative was that “America is the richest, most prepared country on the planet,” he said. “We have this place called the Centers for Disease Control. They’ll handle it.”

The problem with this approach, according to Lewis, is that almost no one aside from Dean and the Wolverines was thinking in probabilistic terms.

“That’s one of the big insights,” he said. “Even people whose job it is to manage risk at some level — and everyone manages risk in their lives — aren’t thinking in hard, cold analytical ways. They are thinking in other ways that distort their judgment.”

Key Takeaway: When assessing risks, calculate probabilities. Don’t rely on narratives.

Finance as a Force for Good

While finance can have a positive influence on the world, Lewis believes the reality is not as straightforward.

The financial sector has been very good at preserving its profitability, he explained. So when innovation comes along and threatens that profitability, the innovation has a harder time gaining traction than it would outside the financial sector.

“[Finance is] a really important part of the economy,” Lewis said. “But the forces for good inside of it have an unusually difficult time getting their voices heard.”

When finance is at its best, generally, it is rather boring, he said.

As for young professionals embarking on careers in finance who want to be a force for good, Lewis had this to say: “Remember who you are now, because you now would never imagine yourself doing the things that you might do three years from now when there’s a lot of money on the line.”

And in the future, when you find yourself facing a “zero-sum moment,” having to choose between doing something that is in your interests financially but not in the best interests of your client, don’t be seduced by the money.

As for those already established in the investment industry, Lewis’s advice was simple: Control your expenses.

“Live a life that is modest enough that if it all goes away, it’s not a catastrophe, so you aren’t in a position where you have to make those bad decisions.”

Key Takeaway: Remember your fiduciary duty and live modestly.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.