Fixed-Income Kryptonite

“Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.”

And he can fly and shoot lasers from his eyes.

Superman not only has the best superpowers, he is also handsome, charming, and humble. Plus he dearly loves his mom and farm.

He might come off a little boring and straitlaced compared to more colorful characters like Ironman or Thor, but he’s clearly the superhero who wins over the most hearts.

One-on-one, no one can outmatch him. Except perhaps someone who brings the proverbial gun to a knife fight. In this case, that gun is Kryptonite, Superman’s only known weakness. The substance renders his powers useless and makes him a normal man — one who can feel pain.

In the investment world, fixed-income instruments have their own Kryptonite: quantitative easing (QE). The central banks’ unconventional monetary policy of buying longer-term securities from the open market to increase the money supply and encourage lending and investment has pushed bond yields in most developed markets toward zero and even into negative territory since the global financial crisis (GFC).

Interest rates have gone negative in Japan, and briefly fell below zero in the United Kingdom. The latter has increased its public debt due to the COVID-19 crisis, which ought to make it less creditworthy. Yet the United Kingdom has just issued its first negative yielding bond.

Over the last 40 years, bonds were the superheroes of investment portfolios. They generated high risk-adjusted returns given steadily declining yields and were mostly negatively correlated to equities and therefore provided attractive diversification benefits. Some investors, such as Ray Dalio at Bridgewater Associates, built their empires on the back of this tailwind.

But with low, nil, or negative yields, how much can bonds still contribute to a portfolio? Has the QE Kryptonite permanently disabled their superhero powers?

The Japanese Example

We could run complex Monte Carlo simulations to demonstrate the impact of low-yielding bonds within asset allocation, or we could simply use Japan as a real-life case study.

The land of the rising sun played an outsized role in the global economy in the 1980s. It reached its apogee in 1989 when its stock market achieved a 45% share of the global market cap compared with only 33% for the United States. But Japan’s economic power was fueled by an asset bubble of epic proportions. It eventually burst, as all bubbles do, and the economy has never fully recovered. Why? Because Japan’s banking system was not thoroughly restructured, which led to a partial zombification of the economy that was made worse by a demographic crisis.

The Japanese government and central bank have taken aggressive and at times unconventional measures to stimulate the economy since the early 1990s. But the long-sought-after recovery is still elusive, and while the banking system has improved, an aging and shrinking population makes the prospects for a full-fledged revival increasingly remote.

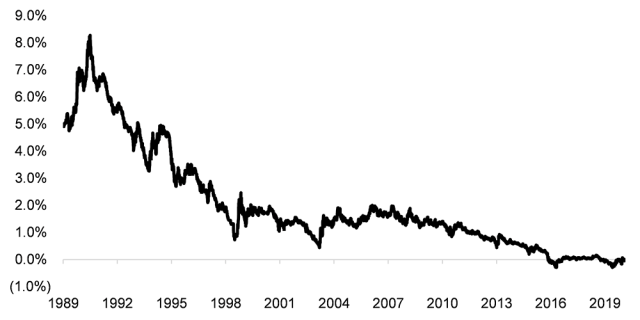

Because of its monetary policy, the Bank of Japan now owns large chunks of the Japanese stock market, and the 10-year government bond first traded at negative interest rates in 2016.

Japanese 10-Year Government Bond Yield

60/40 in a World with Diminishing Superhero Powers

Japan’s 10-year government bond yields fell consistently below 2% after 2000. So 2000 will mark the start of our traditional 60-40 equity-bond portfolio simulation. The Nikkei 225 will be our benchmark for equities and an index of mostly Japanese government bonds our benchmark for fixed income.

Stocks in Japan were up over the 20-year period. But just like their global counterparts, they crashed during the tech bubble implosion in 2000, the GFC in 2008, and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020.

Bonds were negatively correlated to equities in Japan and therefore offered considerable diversification benefits. In addition, bond yields declined from 2% to 0%, generating attractive capital returns. This meant that a traditional equity-bond portfolio delivered higher total returns than a 100% allocation to equities. This same dynamic played out across most developed markets.

Stocks vs. Stock and Bond Portfolio in Japan

Why include bonds in a portfolio? The primary reason is risk reduction. Bonds are, on average at least, less risky than stocks. But most of the financial research highlighting the benefits of fixed-income allocations are based on the last few decades, when structurally declining yields across markets meant bonds had a stand-alone appeal. They were an easy sell.

The case for bonds is less clear amid higher inflation. US fixed-income returns were eaten up by rising inflation during the oil crisis in the 1970s. This meant significant negative real returns for investors. Inflation risk is seemingly remote now, but governments might decide at some point to tackle the global debt problem by allowing inflation to grow rather than dealing with a nasty eventual debt restructuring.

And what’s the rationale for bonds when yields are close to zero or even negative? It’s simply an asset class with no positive expected returns.

Naturally, there are many different kinds of bonds and some, from emerging markets, for example, still offer high yields. However, these come with much higher credit risk and are certainly no free lunch, especially since leverage in emerging markets is at an all-time high across governments, corporates, and consumers.

In Japan, a traditional equity-bond portfolio had lower drawdowns than an all-equities portfolio during the GFC in 2009 and the COVID-19 crisis in 2020. But it was still no improvement to simply hold cash rather than bonds.

Japanese Stocks vs. Stock and Bond Portfolio: Drawdowns

A World without Superman

In one film, Superman died after touching Kryptonite and losing his superpowers. But when humanity was once again on the brink of destruction, he came back to life and saved the planet with the help of a few of his fellow superheroes.

Bonds have touched kryptonite and lost their superpowers, too. And asset owners seem woefully unprepared for a world without them. The average allocation to the asset class has held steady at 30%, almost as if it was on autopilot, since 1999, according to the “Global Pension Asset Study 2020” from the Thinking Ahead Institute. But in the 1990s, Japan’s 10-year government bond yielded 2% and the US 10-year 5%. Today those yields are 0.0% and 0.7%, respectively. That the 30% fixed-income allocation hasn’t changed highlights the underlying absurdity.

Investors have adjusted their asset allocation mix by shifting capital from equities to alternatives. The three stock market crashes over the last 20 years have left deep scars in the minds of allocators. In contrast, during that same period, such alternatives as private equity, real estate, and infrastructure generated attractive and seemingly uncorrelated returns. On paper, they look great and it’s hard to resist their siren call. But alts are no superheroes. They’ve benefited from falling interest rates and represent bets on economic growth. They provide similar exposure as equities.

Global Pension Asset Allocation

Further Thoughts

The funding ratio of US public pensions declined from 74% before the COVID-19 crisis to about 60% currently, according to estimates from Goldman Sachs. Most public pensions still assume a 6%–7% annual return. That is practically impossible with so much of their portfolios invested in an asset class with zero or negative rates and that is hardly risk-free.

And unlike Superman, bonds won’t be making a miraculous recovery and coming back to rescue us. So it’s time to bet on the others, even if they have less appealing powers and are frequently unreliable.

Unconventional times require unconventional asset allocations.

For more insights from Nicolas Rabener and the FactorResearch team, sign up for their email newsletter.

If you liked this post, don’t forget to subscribe to the Enterprising Investor.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

Image credit: ©Getty Images / Devrimb

Professional Learning for CFA Institute Members

CFA Institute members are empowered to self-determine and self-report professional learning (PL) credits earned, including content on Enterprising Investor. Members can record credits easily using their online PL tracker.