Receive free Santiago Abascal updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Santiago Abascal news every morning.

Santiago Abascal, leader of Spain’s hard-right Vox party, repeated one question to his rivals with acerbic intensity. “What is a woman?” he asked in a pre-election debate. For Abascal, an ultra-conservative nationalist likely to be carried to the brink of power-sharing in this weekend’s election, it was a way to fuse two Vox trademarks: a culture war over gender and alarmism over security.

“If you think that a man who perceives himself to be female is a woman,” he said, “then you are wrong. You are very wrong and you put women at risk.” In his sights was a transgender rights law, passed by the Socialist-led government of Pedro Sánchez, which for Abascal symbolises the prime minister’s arrogant detachment from most voters.

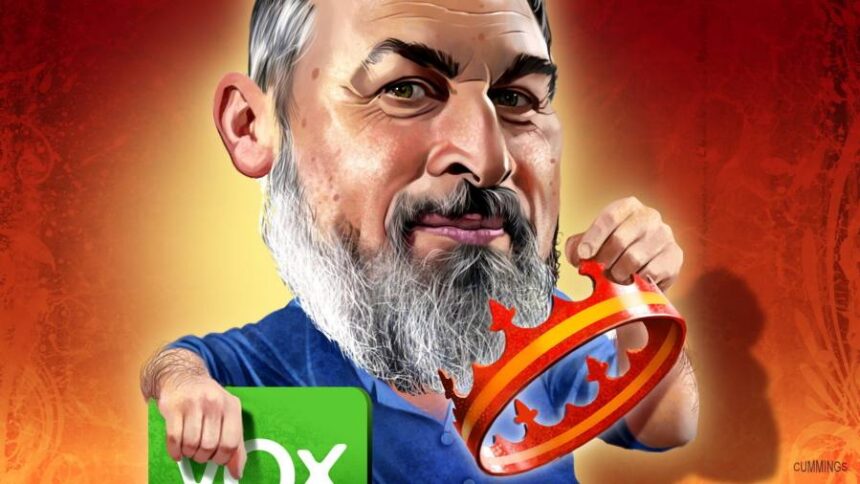

A 47-year-old with a regal beard, the Vox leader combines hellfire bombast with an affable jokiness on the campaign trail, where he pitches himself as a politician who understands the people. Since he took control of the party in 2014, he has taken it from obscurity through a phase of “shy” voter growth to one where its backers are proud to proclaim their support. Vox was the third most popular party in local elections in May and is striving to repeat the feat.

Polls indicate the winner on Sunday will be the conservative People’s party — derided by Abascal as a corrupt, spineless part of Spain’s now defunct two-party system. Its leader, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, is likely to need Vox’s parliamentary support to secure the outright majority needed to take office, despite saying he would rather avoid a coalition. So Spain is asking: what does Abascal want?

One goal is to repeal the transgender bill and a law on gender-based violence, which, according to Abascal, “betray and erase women”. But his push for change extends much further. He dismisses angst about rising temperatures as “climate fanaticism” and wants to burn more fossil fuels. Vox also calls for a naval blockade against migrants’ boats and has warned of a “Muslim invasion” in its anti-immigration campaigns. It wants to scrap laws that have cemented LGBT+ rights, broadened access to abortions and decriminalised euthanasia.

But the most consistent theme in Abascal’s life is hostility to separatists seeking to break away from Spain. Born in Bilbao in 1976, he grew up in the Basque Country in the darkest days of Eta’s violent struggle for independence. His family was under permanent threat because his father was a politician fiercely critical of the terrorist group. The family business, a clothing store in Amurrio, was vandalised and set on fire several times.

“Instead of keeping quiet, we went to the press every time we were attacked. Because it had to be denounced. And the less we kept quiet, the more they attacked us,” he once said.

Abascal recalls watching bodyguards check the family car for bombs before leaving the house. When he was nine, Eta shot dead the local postman, a friend of his father. “That put my life on the path towards politics,” he said.

At university he studied sociology, railing against nationalism and its use of myths, the Basque strain included. He quoted philosopher Karl Popper in his dissertation, saying nationalism “flatters our tribal instincts, our passions and prejudices”.

“Everything he criticises about Basque nationalism he has reproduced in Spanish nationalism,” says Miguel González, author of Vox Inc., a book about the party. “He’s either a cynic or he has the memory of a goldfish.”

Abascal joined the PP but in 2013 was part of a group who quit the party in order to found Vox, disgusted over corruption and then prime minister Mariano Rajoy for not taking a tougher line against separatists. José Luis González Quirós, another Vox founder, said the original goal was to pressure the PP into changing. But when Abascal took control, he put the party on a different path.

“Abascal is a shrewd and ambitious guy,” González Quirós says. “He saw an opportunity in the fact that the right had neglected part of its public, and he installed himself to take advantage of it.”

To keep Vox alive, Abascal took donations from hardline Catholic groups opposed to abortion and gay marriage. The party’s breakthrough came in 2017 when a Catalan push for independence exploded over an unconstitutional referendum, galvanising opposition to separatism in the rest of Spain and sending voters flocking to the party.

Vox has its own internal factions. On economic policy, its pro-market liberals disagree with its protectionists and state interventionists. Some Voxistas bristle when the party is described as a throwback to Francisco Franco’s dictatorship but Abascal has said there is a place in the party for “others who defend Franco’s work”.

Since the 2019 election, he has allowed those who care about closed borders and Catholicism to gain the ascendancy. He has tried to soften some hard edges in the present campaign, but where Vox is already in power with the PP in local government it has eliminated environment and equality departments and banned LGBT+ flags on public buildings.

How many votes Abascal wins on Sunday will determine whether he has to make concessions to govern with the PP at national level, or whether Vox will lay down the law. When one voter urged him to “fix things” on a visit to a market, he replied: “It’s not gonna be easy. I’m not gonna deceive you like the others.”

barney.jopson@ft.com