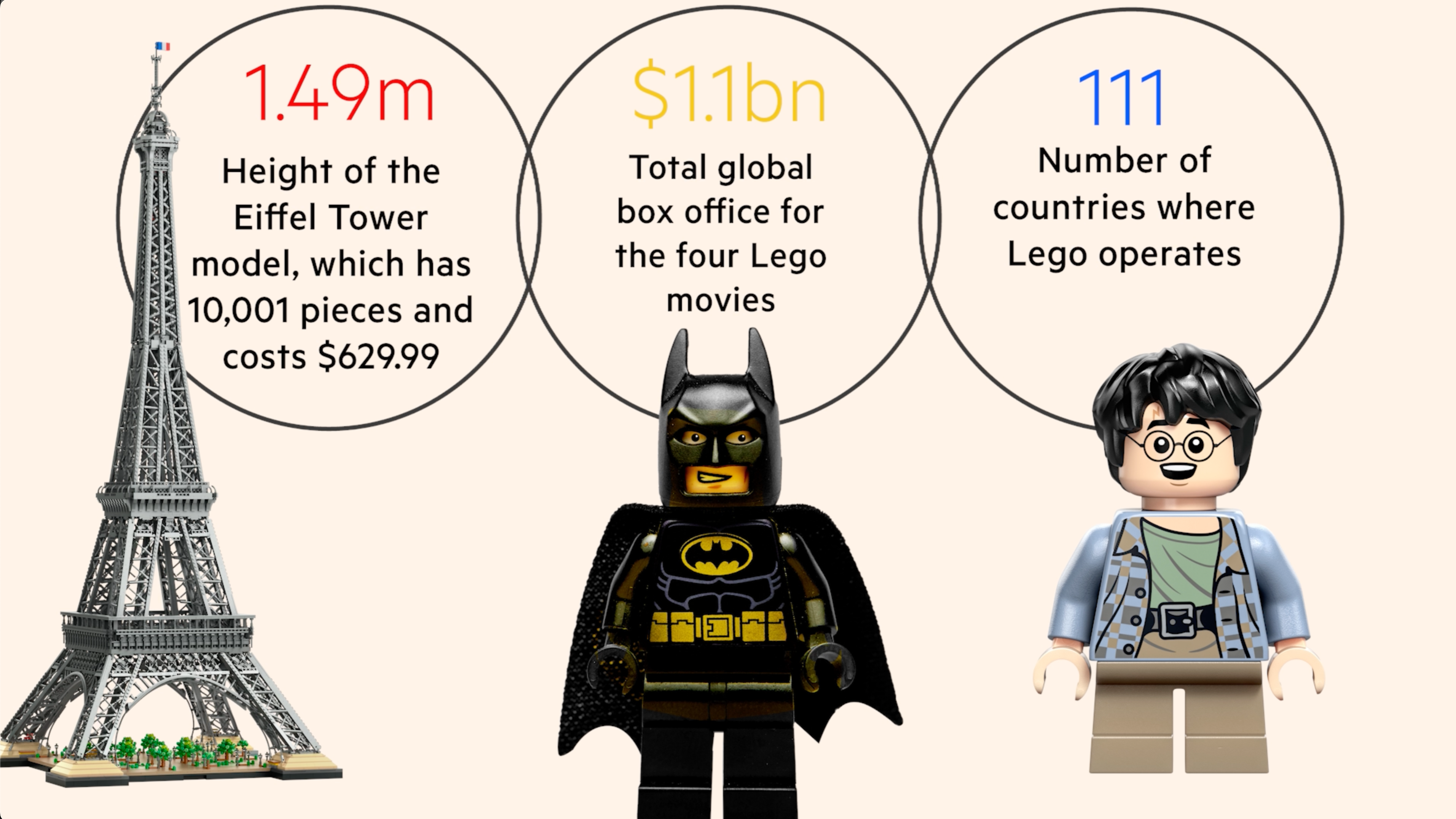

Look closely at Lego’s version of a bonsai tree and you will see that many of the blossoms are made from plastic bricks shaped as pink frogs. Similarly, on its model of the Eiffel Tower, the in-house designers turned to an unusual Lego piece: the hot dog sausage.

Jens Kronvold Frederiksen, design director for the Star Wars line at the Danish toymaker, laughs as he details the resourceful, and sometimes just plain comical, ways his colleagues repurpose existing plastic bricks to make new objects and keep costs down. Its popular Botanical Collection — which interprets orchids, wildflowers and bouquets using Lego — reuses pterodactyl wings, robot heads and car bonnets to mimic various parts of nature.

Such innovations have propelled the family-owned toymaker to become one of Europe’s biggest corporate success stories of the past decade. Lego, with essentially just one product in endless iterations, has raced past Mattel and Hasbro — the listed US companies with stables of hundreds of different toy brands — to become by far the biggest toymaker in the world by sales, and on a different level altogether in terms of profits.

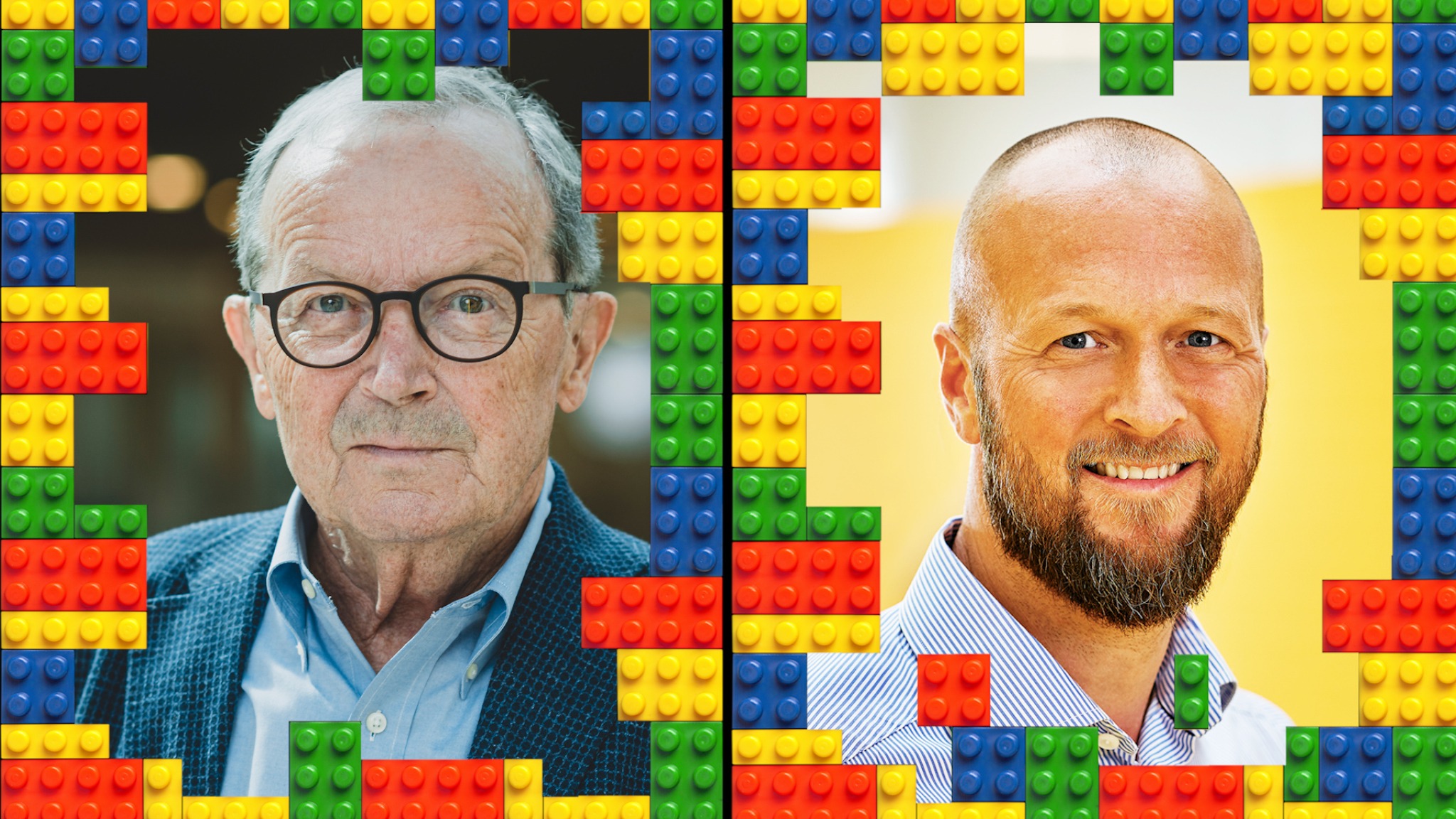

At the same time, Lego quietly completed a transition in its family ownership — the bedrock of the company — this year. Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, a former Lego chief executive and main family powerbroker for almost half a century, passed on the mantle to his son Thomas, the fourth generation to run Lego in the small Jutland town of Billund.

“The ambition level is super high — we want to have that impact on every child in the world that we can reach,” says Thomas, who is now chair of Lego as well as Kirkbi, the family investment vehicle that controls the toymaker, in a rare interview.

The challenges facing Lego appear formidable — the global toy market has long seen little or no growth as children flock to digital devices for play and entertainment; its iconic plastic bricks are proving harder than expected to rid of oil. But the Danish company is in strong shape financially with sales and net profits that are up more than seven-fold since 2006, and with the committed backing of its long-term family shareholder.

Lego is no longer a pure toymaker. Its products appear in TV shows, films, apps and theme park rides with storylines pitched at boys, girls and, increasingly, adults. “Lego is less about brick-based construction and more about being a talent agency for mini-figures,” says David Robertson, author of the leading book on the company, Brick by Brick.

Its revenues — including the Legoland theme parks, controlled separately by Kirkbi — are almost as high as Mattel’s and Hasbro’s combined. For many inside and outside the company, the most obvious rival is now the far bigger Disney.

“We have to look at ourselves as an entertainment brand. Our brand characteristics are much more like Disney, the brand strengths are much more like Disney than any more traditional toy competitor,” says Niels Christiansen, Lego’s chief executive who is no relation of the founding family.

Building blocks

Lego celebrated 90 years as a company in 2022, but it only got into plastic bricks in the 1950s having started out in wooden toys.

The strength of its system of play is that all of its bricks are compatible with the others regardless of the decade in which they were made. During a tour of its factory, the company produced a recently recovered brick from 1962 which remains usable today.

But Lego’s history is not one of uninterrupted success. The company almost collapsed around the turn of the century under Kjeld’s leadership: it lost faith in the brick and started offering products that looked more like Barbie or Action Man, which backfired.

In an effort to save the company, an outsider, Jørgen Vig Knudstorp, was hired as chief executive, a back-to-basics policy was instigated with the brick at the heart of things, and Lego has barely looked back.

Sales in 2006 were about $1.3bn, almost a third of Hasbro’s and a quarter of Mattel’s. Its profits were about the same as Hasbro’s and half Mattel’s, who produce Transformers and Barbie, respectively.

Today it is a different story: its revenues last year were $9.1bn compared with $5.4bn at Mattel and $5.9bn at Hasbro. Lego’s net profit of $1.9bn was well above Mattel’s $390mn and Hasbro’s $200mn, both of whom were below their 2006 levels — although Mattel could receive a boost this year from the Barbie film.

Profits in the first half of this year dropped by a fifth at Lego (against losses for the other two toymakers), but Christiansen says this was planned. Profitability soared to unsustainable levels during the Covid-19 pandemic, and Lego decided to invest heavily in digital and sustainability.

“Imagine: when I started in October of 2017, I would get a question: do you think the brick is still relevant, or is it coming to an end? I’ve not had that question one single time in the last three or four years,” says Lego’s chief executive, under whose watch the company has consistently taken market share.

Lego has increased the number of sets it sells dramatically. Once focused around a couple of homegrown product lines such as the police stations in its City range and warriors of Ninjago designed to appeal to young boys, alongside a few select film tie-ins such as Star Wars and Harry Potter, Lego is now much broader.

It has several ranges marketed at girls and numerous huge sets for adults from football stadiums and cars to the Titanic and Concorde. DreamZzz, the first range targeted equally at boys and girls, came out this year along with a new TV show. Other products such as the Super Mario range work with their own apps.

It has rapidly increased its retail presence. Partially as a consequence of the bankruptcy of Toys R Us in 2017, Lego has expanded its network from 317 stores that year to about 1,000 currently.

Christiansen says there is no upper limit as Lego aims to reach children worldwide, with a particular recent push in China, both with stores and a range — Monkie Kid — designed specifically to appeal to local customers. Legoland theme parks are expanding too.

Not everything has worked well — Robertson notes that their “phygital” sets, designed to bridge the gap between physical and digital play, have fared badly with expensive flops such as Nexo Knights, Hidden Side, and Vidyo.

“They have a tremendous amount of resources to cover those failures. More power to them for investing in risky things that open up new potential areas for growth,” says Robertson, who is also a senior lecturer on innovation at MIT Sloan. “Lego are a great example of how little innovation experiments can become huge growth opportunities.”

The art of succession

Backing Christiansen has been a founding family undergoing a transformation of its own.

Kjeld, head of the third generation, was the last to hold a management role at Lego, deciding that the family’s future instead lay in being an active owner.

Since 2016, he has gradually stepped back from post after post, completing the transition to his son Thomas in May. Throughout, the family has been mindful of avoiding the squabbling that often besets family businesses as they are passed down the generations.

The family has worked with the Swiss IMD business school to develop a family constitution and make sure that each generation becomes engaged with Lego.

“In my generation we are three people, in the next generation there are seven, and in the next one there will be even more,” says Thomas. “It’s important to create a structure where the family itself doesn’t become a liability. Because we also know that most often it is the families themselves that destroy the companies they own because they can’t get along or disagree on the direction.”

He was designated his generation’s “most active owner”, meaning he has taken on the role of chair at Lego, Kirkbi and the charitable Lego Foundation that also owns a quarter of the toymaker. A new fund called K2 was set up with a low amount of capital but a high number of votes, so if there should ever be disagreement in the future, it would vote alongside the most active owner to push change through.

Thomas is already thinking about passing on to the next generation, even if they are aged only two to 17. He has set up a Lego School, which aims to inculcate them with the values and challenges of the toymaker as well as the specificities of running a family company: “It’s simply about equipping them and preparing them as well as we can,” he says, adding that “it’s done in a very playful way so they think it’s fun and want to take an active owner role in the future”.

That stems from his own “mixed feelings” growing up in Billund where Lego is a big employer. His parents tried to protect him and his siblings from the business, but at times it could be awkward. “Most of the times it was great when things were good. But when things were not so good, it wasn’t fun at all,” Thomas says, referring to the period in 2003 when his father had to make job cuts, including those of his friends’ parents.

The first board meeting he attended at the end of 2004 was an eye-opener. Lego was still in crisis, even if its young chief executive Knudstorp was putting in place what would become a successful turnaround. “Everyone apart from my father said, ‘This isn’t going to work, we have to sell.’ He held on to the idea that there must be more to it than this. So there have been bumps,” says Thomas.

Christiansen credits the family with staying the course, particularly during the pandemic, whereas many listed companies took short-term decisions to cut investments to shore up profitability. “It’s harder to consistently build a brand like Lego if you’re listed. You saw some major brands during the pandemic, in order to protect the bottom line, overreact on things that actually hurt the brand,” he says.

The chief executive stresses that Lego’s board still discusses profitability, but is more willing to stand by big investments, such as its recent decision to triple spending on sustainability.

“I don’t want to leave this impression that it’s just easier or nice, it’s probably more that you can stand through the bigger investments a little better. And if you do it that way, the return will also be better,” he adds.

For Thomas, sustainability is particularly important for a brand focused on children. It requires 2kg of petroleum to produce 1kg of plastic, and he is keen to move to renewable sources.

Finding a new solution to this existential predicament remains a concern. “The raw material that we rely so much on is based on the wrong thing. It’s a big thing to change that,” he adds. “It has been tough because it goes against the logic of a normal business to push very hard on something that has no return for the next year or years.”

But Christiansen says Lego will back many partners and initiatives to find greener plastics. “Here is a place where family ownership can help,” he adds. “We may take a bigger load than most companies will early on to get the ball rolling.”

‘Make it larger’

There is a new assertiveness about Lego.

Previously, its headquarters in Billund were a drab office building. Now it has a bright new campus — replete with start-up-like touches such as a mini golf course on the roof, baristas doling out free coffee, and a hotel for visiting employees — with a giant mini-figure outside.

“Kjeld said, ‘Make it even larger,’” says Timothy Ahrensbach, director of workplace and employee experience, of the Lego statue. Lego House, designed by the world-renowned architect Bjarke Ingels, plunges visitors into a world of bricks, where even the food comes served in them.

That confidence extends to corporate deals. Legoland theme parks were sold off in 2005 as part of the turnaround, which pared the toymaker back to its core, but are now back under Kirkbi control.

Another Lego Movie — the franchise’s four blockbusters collectively made more than $1.1bn worldwide — is “a possibility,” says Christiansen, although he adds that he never wants to “become predictable”.

Meanwhile, Thomas’s ambitions for Kirkbi, which also owns stakes in several large Danish blue-chip companies, transcend Lego. The investment vehicle recently bought a digital learning platform in the US, and he is clear that education is a way of reaching children it cannot through the toymaker and its relatively expensive Lego sets.

Lego is building new factories in the US and Vietnam — to go alongside its present ones in Denmark, Hungary, Czech Republic, Mexico and China. It is working on a partnership with Epic Games, the makers of Fortnite, to develop a Lego experience in the metaverse.

And all the while it is expanding its product portfolio. Cerim Manovi, the creative lead for one such new line called DreamZzz, says he worked on the project for four years, testing 50 different ideas with 15,000 children to develop a new homegrown range for Lego.

Finally, his team came up with a dream world inhabited by a series of mash-ups such as a crocodile car, a shark ship and a turtle van. Each set has instructions to build the model 80 per cent of the way, and then gives them a choice on how to finish it off. “We call it ‘guided creativity’,” he says, an attempt to head off complaints Lego’s sets no longer encourage imaginative play.

Christiansen says that Lego may be experimenting thanks to its newfound financial strength, but that it is doing so in a focused way. “We can do experiments, but I would rather do fewer things and do them right rather than end up with many initiatives, none of them fully fledged. Because we know what works, and then we invest money behind it.”

For Thomas, there is much more ground to conquer. He say: “My father always said we are more than a toy company. Everyone has always said: ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, but you are a toy company.’ But I think the potential and the idea are about so much more.”

He sees Lego’s competition as “everyone out there who takes time from children”.

Robertson, the academic, agrees that Lego — with toys, TV shows, films, and theme parks — is starting to resemble Disney, which had $82.7bn in revenues last year.

“Disney is so much bigger than Lego — and that’s a huge opportunity. Lego can pick and choose how they go after that,” he adds. “You start with this small plastic brick company, and now you have movies, theme parks, digital — someday it could be as big as Disney.”