Receive free Russian politics updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Russian politics news every morning.

The Russian authorities’ determination to silence Alexei Navalny seems to know no bounds. First, they poisoned the opposition leader with the nerve agent novichok (and the evidence points overwhelmingly to Russian security agents). Then, after he returned to Russia from treatment in Germany, they jailed him for nine years on bogus fraud charges. Now he has been handed a further 19-year term on charges of “extremism”.

Navalny’s treatment is outrageous. Yet it is only the tip of an iceberg of convictions against critics of Vladimir Putin, plus detentions and harassment of thousands of people who have protested against Russia’s war in Ukraine. A side-effect of the conflict is that the Kremlin is stepping up efforts to intimidate its citizens, in ways that hark back to the darkest days of the last century.

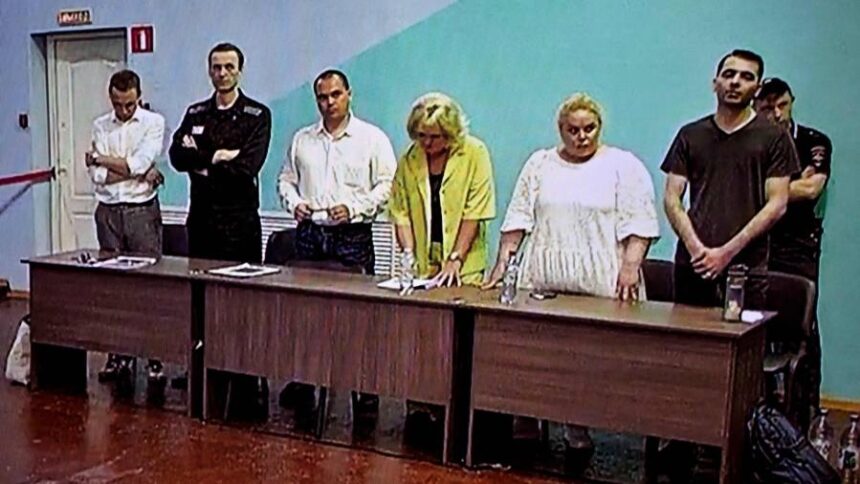

The latest case against Navalny is grimly typical. Already in jail, the opposition leader was presented with a 3,828-page dossier of further alleged crimes that in effect criminalised all his anti-corruption foundation’s activities since it opened in 2011. Though Navalny showed great courage in returning to his homeland — seemingly convinced that only from inside Russia could he exert maximum influence — his latest conviction will send him to a “special regime” prison colony, where he will be even more cut off from the outside world.

Several employees of his anti-corruption group who have not left Russia are behind bars too. One, Daniel Kholodny, was moved from another prison to stand trial alongside Navalny and sentenced to eight years in the same case. Two heads of Navalny regional offices, Lilia Chanysheva and Vadim Ostanin, and another associate, Rustem Mulyukov, have been sentenced since June to between two and a half and nine years.

Beyond the Navalny circle, Vladimir Kara-Murza was jailed for a shocking 25 years in April under a newly broadened treason law and for “discrediting” the Russian military in speeches and articles — made a crime last year. A dual British national, Kara-Murza is a former ally of Boris Nemtsov, the opposition leader shot dead near the Kremlin in 2015. The columnist for the Washington Post survived two poisonings in Russia and was repeatedly tailed, according to the investigative website Bellingcat, by the same team of security agents that poisoned Navalny.

Also on trial for discrediting Russia’s military, Oleg Orlov, a co-chair of the Memorial human rights group, could face a three-year sentence. And not just Russian activists are targets. Evan Gershkovich, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, was detained by Russian security services in March, the first American journalist held in Russia on espionage charges since the cold war.

Up to 20,000 Russian citizens, according to a report last month by Amnesty International, have meanwhile been subjected to heavy reprisals in a campaign to silence criticism of the war in Ukraine. Authorities, it says, have used administrative and criminal charges as well as dismissals, intimidation, and designating critics of the war as “foreign agents”. Memorial’s Orlov says the number of cases is reminiscent of the Brezhnev era in the 1960s and 1970s. But in its cruelty and length of prison terms, it is “like Stalin’s time”.

Western leverage in Russia is at its lowest since the Soviet collapse. But foreign companies still doing business there should waste no further time in pulling out. Politicians and diplomats should use all opportunities to express solidarity with the Russian democratic opposition. Governments must swallow their distaste if opportunities arise to exchange jailed Russian spies or criminals abroad for people wrongfully detained in Russia. In the end, however, this lurch backwards in the rule of law will be another corrosive effect of Putin’s war for his own society that will take years to reverse.