If an entire industry could heave a sigh of relief, it would be the UK car sector.

India’s Tata Group on Wednesday ended months of suspense with news that it would build a £4bn gigafactory in the UK, which will be big enough to supply not just its own luxury carmaker Jaguar Land Rover, but other customers.

To the surprise of many in the sector, a British government that has expressed its discomfort with industrial policy managed to outbid a less squeamish rival, Spain, for one of the most prized investments in the European motor industry.

UK prime minister Rishi Sunak unveiled the deal on Wednesday with Natarajan Chandrasekaran, chair of parent company Tata Sons, at JLR’s factory at Gaydon in Warwickshire. Grant Shapps, UK energy secretary, admitted that the government financial support on offer was “large”.

At an estimated capacity of 40 gigawatt hours, Tata’s planned gigafactory at Bridgwater in Somerset will be “twice the size of the average battery plant”, said Stephen Gifford, chief economist at the Faraday Institution, a research body focused on electrical storage technologies. It would also supply 40 per cent of the expected demand for batteries from UK carmakers by 2030, he added.

The motor industry is cockahoop. “Tata were looking at Spain and the fact that they have chosen the UK is a shot in the arm for us,” said Mike Hawes, chief executive of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, the British trade body for carmakers. “This battery production will help to put the UK back on the map, which has been pretty tough in the past few years.”

“This has got to be good news,” added one UK car industry executive who preferred not to be named.

The industry’s hope is that the government’s clear display of support for Tata’s gigafactory — estimated to come to about £500mn — will encourage others to invest in electric vehicle production in the UK after a period of uncertainty created by political turmoil and post-Brexit complexities.

“The narrative around the automotive industry has been negative for the past few years,” said Hawes. “Political, economic and regulatory uncertainty have made investment in the UK very difficult.”

Even some of Britain’s oldest overseas investors have been scaling back. Ford in 2020 closed its engine factory in Bridgend, while Honda shut its plant at Swindon in 2021. Last year UK production fell to its lowest since the 1950s, at just under 800,000 vehicles, far from the peak of 2mn in the 1970s.

Industry has criticised the government for failing to develop a consistent vision for the UK transition to electric vehicles, while at the same time imposing nigh-impossible constraints on petrol and diesel cars.

The UK will ban the sale of new cars with combustion engines from 2030 and require manufacturers to meet electric vehicle sales targets from next year.

In addition, post-Brexit trading arrangements that require electric vehicles to contain 45 per cent EU or UK content from next year or face 10 per cent tariffs risk making the industry uncompetitive just as Chinese electric-vehicle makers are stepping up their presence. The British ecosystem is far from ready to fulfil those demands, according to industry executives.

Competitive batteries are the most critical part of that ecosystem. According to the Faraday Institution, Germany has 12 battery plants in the works, the biggest at 100GWH.

Until the Tata announcement, the UK had only a 12GWH plant planned by Japan’s Nissan in Sunderland with China’s Envision battery maker, and an older 2GWH plant on the same site.

Plans for a gigafactory at Blyth in Northumberland fell apart early this year when battery start up Britishvolt collapsed into administration. Parts of the company were subsequently bought by an Australian group, with the promise of reviving the plans.

Tata’s investment in Somerset could be the catalyst for change, however. It not only will support JLR’s transition to electric vehicles, but also secure the UK supply chain as well, said Hawes. Tata said the batteries will be designed and produced by Agratas, its new global battery business.

“It is tremendously important for the industry as a whole,” added Hawes. “It is massive for JLR and others will have the potential to benefit if we can get the supply chain going.”

Kevin Shang, analyst at Wood Mackenzie, a research firm, said the Tata announcement could “stimulate” the UK manufacturing of cathode and anode components for batteries. However “UK battery plants will have to rely on imports from east Asia, especially Chinese and Korean companies, to meet their demand” in the short term, he added.

There may also be questions about whether the UK is betting the revival of its motor industry on the recovery of one company — JLR, which is the UK’s largest car manufacturing employer, producing roughly 25 per cent of the country’s vehicles.

The gigafactory is first and foremost designed to answer the needs of JLR, which has pledged to invest £15bn in delivering six new all electric models as part of its own recovery plan.

After launching one of the earliest electric vehicles, the I-Pace in 2018, JLR failed to expand the range. High costs and a misguided strategy of chasing volume had left JLR nursing heavy losses, said Charles Tennant, analyst and a former Tata executive.

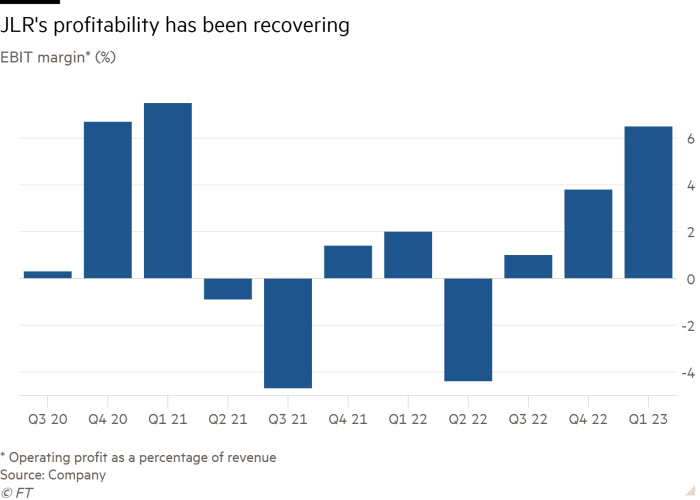

But that is now changing after JLR opted to cut costs, reduce volume and increase pricing. Although the company made a loss of £64mn before tax and exceptionals in the year to end March 2023, this compared to losses of £412mn in the previous 12 months.

In the current financial year, JLR is set to report three consecutive quarters of profit, said Tennant. And its breakeven point has halved to 300,000 units a year while the average selling price has risen from just over £40,000 to more than £70,000.

The challenge for JLR will be to maintain that trend in the transition to electric vehicles, said Dom Tribe, analyst at Vendigital, a consultancy. “It will be very telling when they bring new all-electric Jaguars to market with a six-figure price point. Are customers willing to spend £100,000 on an electric Jaguar?”

But even if it is a gamble on Tata and JLR, the UK needs the gigafactory in Somerset if it is to have a motor industry with a future. “This is really a renaissance of UK industry,” said Tennant. “It’s taking the industry into the electric vehicle age.”